meanderings

Mud then cobbles and more cobbles, the hike from Fern Cove south to Cove on Colvos Passage tours Vashon’s best beach forms. The first wonder is Fern Cove’s delta, then Peter Point’s salt marsh and finally the big rock before Cove.

For beach access, a muddy path is cut through the shrubs at the end of Fern Cove’s long driveway. Within feet, if low tide, the expansive delta fans out into Colvos Passage. No sunshine is needed for the vista to shimmer with light.

Meandering through this shield, salmon-bearing Shinglemill and Baldwin creeks replenish the delta with sediment and organic nutrients from the Island’s forested interior. The sediments build faster than the waves erode them.

Birders love Fern Cove Preserve. Its conifer forest, alder gangs, salt marsh, mud flat and sheltered full tide host varied birds such as the woods’ brown creepers and winter wrens to yellowlegs, terns, dunlins and the rarely sighted spotted sandpiper, black turnstones and long-billed dowitchers.

To hike south, skirt the wetland on the south, wade Shinglemill Creek (but not during November’s salmon migration) and keep to the upper beach’s cobbles. Even the most savvy lose boots in the delta’s terraces and creek-cut muck.

To the south, the beach tends southwesterly. Roses and mock orange perfume the air. Thimbleberry and native blackberry bloom, and salmonberries ripen. This year, the salal’s blooms are myriad — pink, perfect bells.

But soon hikers forget all that is lovely. They neglect to scan Colvos Passage or the view north to Southworth. Footfall requires all attention. Here, no sand strip appears on a minus tide to speed traversing; sea lettuce and popweed slick the mid-beach. Cobbles relentlessly pave the beach from wave break to bank. The easiest path is top beach, the whole way from Fern Cove to Cove and back.

The bulkheads before Peter Point feature mammoth greenstone, a metamorphosed basalt, most likely from north Puget Sound’s Mats Mats Bay. Behind the bulkhead, small spaces are filled with spalls (smaller rocks). On this beach, patches of greenstone spalls decorate the beach, strewn like crushed black pepper on the native cobbles’ monotone. Spalls escape the bulkheads, either by wave action or bulkhead failure.

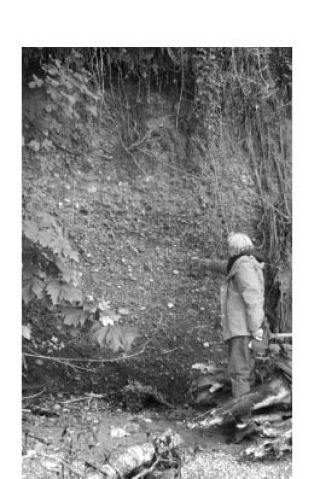

In a gap between bulkheads, a cliff exposure reveals the source of the native beach material. A wall of well-rounded, horizontally aligned cobbles are embedded in sand and gravel. Stratified layers indicate origin under varied stream conditions, such as a fast or slow-moving flow. The U.S. Geological Survey maps this cobbly bluff as a river outwash deposit, from a glacial episode older than 18,000 years, so prior to the most recent Vashon glaciation.

Peter Point ends this beach dramatically. It sits seemingly high, with a steep front and narrow girth. Cut by waves, its slope resembles smoothed coils of a hand-crafted pot. To build Peter Point, sediment from unarmored shore is picked up and carried from the south by a nearshore current, or drift cell. A much shorter drift cell also flows to the point from the north. The opposing waters’ convergence is visible immediately off shore.

The point’s interior holds a salt marsh distinguished by a pond of open water. This feature is so rare that recently King County’s Greenprint survey designated it as a “priority area for future protection.”

Native Americans called it Qu’;ti or “sleeping mats,” for its cattails used in weaving. I see no cattails, but Scotch broom circles the interior, and rugosa roses mound on its front edge. Swallows cruise in over the pond. (Look from the beach only. The marsh is private property.)

From here to Cove, the shore pattern repeats itself — cobbled stretches and coves between points. Always in view in the shallows ahead, a neon-green daymark guides boats with a flashing beacon.

In March 1938, Islander George McCormick boasted he could walk the Vashon-Maury shore in less than 24 hours. Sixty-seven dollars was his if he succeeded. Historylink.com reports that he hiked counterclockwise starting at Tahlequah at 10 a.m. From 11 p.m. to 1 a.m., he crossed the cobbles from Colvos to Cove, slowing to one mile an hour from his average of three miles an hour. He ended his 65-mile trip at 6:50 a.m. in a total time of 20 hours and 50 minutes. In 1966, Charlie Brough beat the McCormick record with a time of 15 hours, 52 minutes.

In the 1950s, Islander Shirley Speidel and friends hiked the Island section by section. Daughter Sunny remembers her mom’s hikes as “a girls’ event.” Will this round-the-Islands tradition be impossible if Glacier’s gravel operation closes its beach on Maury’s shore for safety reason as it loads its barges?

Soon after rounding Peter Point and its southerly beach, another cove appears. It is bright with the varied greens of fir forest, willow wetland, country garden and salmonberry wilds. Most of its shore is unarmored, and the houses spread inland up the valley. The next cove must boast of more rock wall than a small municipality. The northern section is Wilkerson sandstone from a quarry near Mount Rainier, and the rest is the ubiquitous greenstone. To soften the human footprint, a fawn jumps into the shrubs, and goslings stubbornly ignore human passage.

Ahead, a dock hosts purple martin nesting boxes, then another steep-sided point leads onto the beach before Cove. A mammoth rock offers itself as a fine perch for a respite before the cobble hobble back to Fern Cove. Big cedars dominate the woods, and a garden-variety willow spreads out, its limbs kneeling on the beach as if in adoration of Colvos’ marine paradise. Another Colvos acolyte, Islander Jack Barbash, is leading a local effort proposing that the Washington state Department of Natural Resources designate Colvos Passage as an Aquatic Reserve.

An hour-plus later, back at Fern Cove, I hear a rustle in the fir forest in spite of no wind. A tall fir appears to step forward, and its sister trees’ branches briefly hold it. Then the 40-footer falls with a swoosh. I saw — and heard — the proverbial tree fall in the forest.

— Ann Spiers is an Island poet and naturalist.