Editor’s Note: Steve Bergman’s commentary is the latest in a series of “Green Briefs,” presented in partnership with the Whole Vashon Project. To find out more about the group’s work, visit wholevashonproject.com.

Traditional economics measures success using parameters such as the gross domestic product (GDP), which ignores negative impacts on the environment and health.

In addition, GDP growth is a central tenet despite its conflict with sustainability and finite planetary resources.

We need a new way to measure the quality of life and prosperity.

We inhabit a dynamic, near-spherical planet with complicated and interrelated earth systems. Although Earth has experienced many changes during its amazing 4.5-billion-year history, including developing an oxygen-bearing atmosphere in which photosynthetic cyanobacteria (ancestors of plants) evolved more than 2 billion years ago, its environment has been remarkably stable since the end of the last ice age.

Over the last 10,000-year period of stability, human civilizations have arisen, developed and thrived. However, in the last two centuries, since the rise of the Industrial Revolution, human activity has become the main driver of global environmental change, impacting and harming Earth and her animal and plant life on a global scale.

How can we fairly meet the needs of Earth’s inhabitants within our finite planetary boundaries? How can we be sure that no one falls short on life’s essentials (from food and housing to healthcare and political voice), while not overshooting our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems on which we fundamentally depend? These systems include, for example, essentials such as a stable climate, clean water and air, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer.

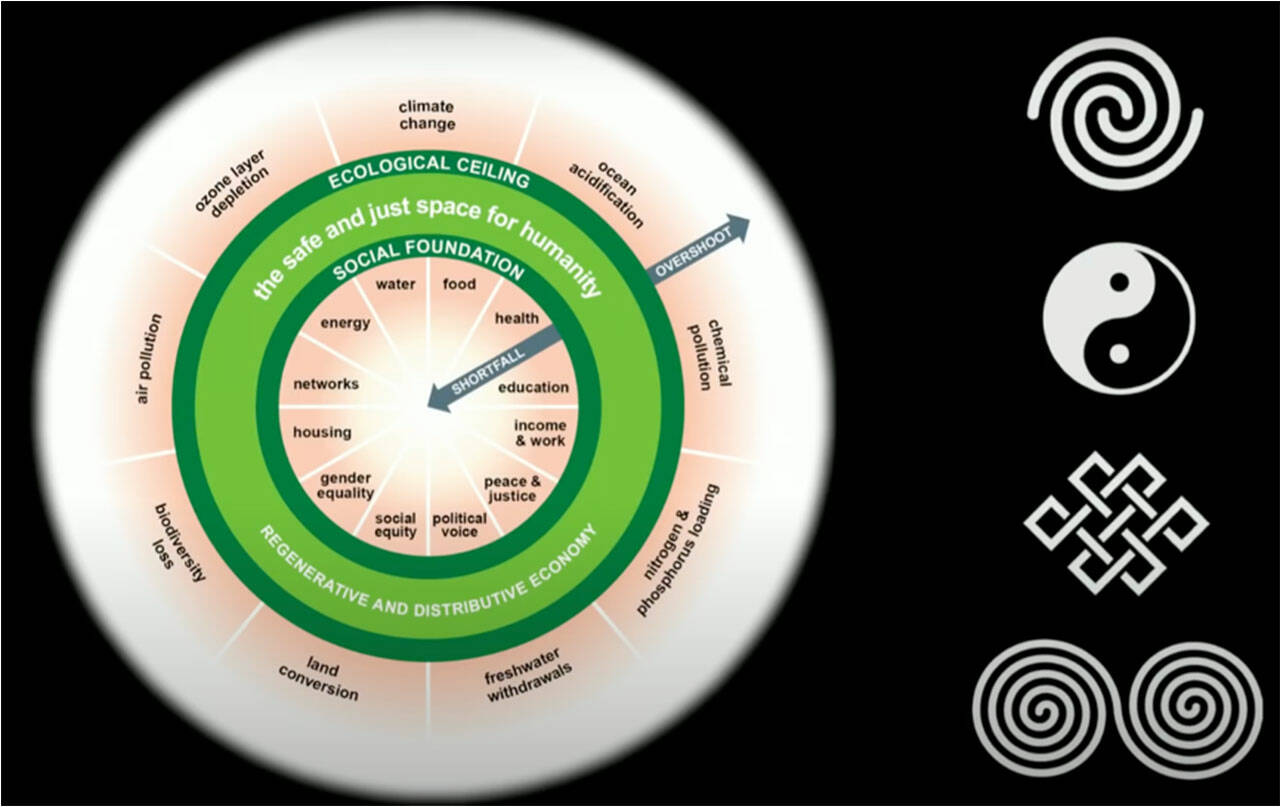

The English economist Kate Raworth offers a solution in her “Doughnut Economics” framework. She argues that 20th-century economic thinking is not able to deal with the 21st-century reality of a planet experiencing a climate crisis. She suggests that instead, we guide our future choices with a model that is like the conventional doughnut shape of a squashed sphere with a central hole as the inner limit.

The outer limit of Raworth’s economic doughnut represents nine planetary boundaries or ecological limits: climate change, change in biosphere integrity (biodiversity loss and species extinction), stratospheric ozone depletion, ocean acidification, biogeochemical flows (phosphorus and nitrogen cycles), land-system change (eg., deforestation), freshwater use, atmospheric aerosol loading (microscopic particles in the atmosphere that affect climate and living organisms), and introduction of novel entities (e.g. organic pollutants, radioactive materials, nano-materials, and micro-plastics).

Unacceptable environmental degradation and potential tipping points in Earth’s systems are likely if these ecological ceilings are exceeded. In fact, many of these have already been surpassed, and some of them could shift the planet into a new state with potentially disastrous consequences for humans. (People in richer countries are already living above the environmental ceiling.)

The inner limit of Raworth’s model comprises twelve dimensions of internationally agreed-upon minimum social standards (the United Nations’ 2015 Sustainable Development Goals): food, water/sanitation, energy, health, work/income, peace/justice, political voice, social equity, gender equality, housing, and networks. The actual doughnut itself is the environmentally safe and socially-just space in which humanity can thrive and prosper. Outside of the doughnut is to be avoided. (And in general, people in poorer countries are already beyond the safe zone’s inner limit.)

Can we apply the benefits of a Doughnut Economics model here on Vashon Island? You bet we can — by delving into the model and learning enough to promote it. Raworth recommends starting with “seven ways to think,” each forming a chapter in her 2017 book:

1) Change our economic goals from a rising GDP to the Doughnut model.

2) See a bigger picture of an embedded instead of self-contained economy.

3) Nurture human nature, by moving from rational/economic to social/adaptable humans.

4) Get savvy with Earth’s dynamic systems/forget mechanical equilibrium.

5) Design to distribute goods/food with minimal environmental impact.

6) Create to regenerate.

7) Be agnostic about growth.

We can share her model with relatives, friends and colleagues. We could combine Doughnut Economics with principles of a “circular economy,” which reduces, reuses and recycles materials across consumer goods, building materials and food.

Many island initiatives, including the Vashon Tool Library, Vashon Care Network and others have already started along this path.

The bottom line: We can work to get policies enacted that protect the environment and natural resources, reduce social exclusion, promote social equity and guarantee good living standards for all.

Raworth nicely summarizes her theory by saying, “A healthy economy should be designed to thrive, not grow.” It is time to shed the old economic growth model and replace it with one more sustainable and equitable. Raworth’s model offers just that.

We invite you to visit Doughnut Economics Action Lab, at doughnuteconomics.org for much more detail.

Steve Bergman is a geologist, Zero Waste Vashon and Vashon Makerspace board member and Whole Vashon Project advisor.