I grew up in New England where the colonists arrived on this continent in the early 1600s. When I traveled on certain roads I would sometimes see these small stone markers on the side of the road. They looked kind of like little tombstones with words and numbers etched into them. They were milestones and would note the distance to Boston or Sudbury or to the nearest town.

The term “milestone” has entered our vernacular as a way to acknowledge an important event, like a graduation or a wedding or retirement after a long career.

When I was first diagnosed with cancer, I didn’t know that I would be reaching certain milestones.

But I knew that after several treatments of chemotherapy, my hair would start to fall out. I knew that people with cancer lost their hair because I’ve seen them wearing stocking caps or scarves on their heads in the summer.

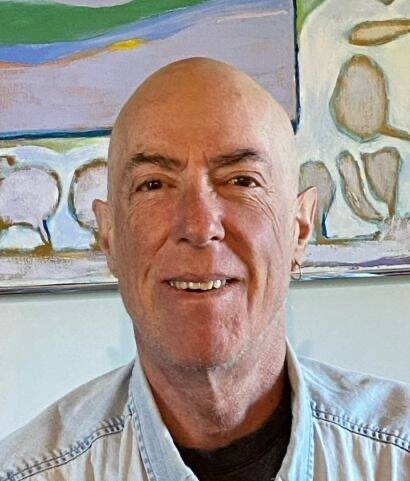

When I saw my soapy hands covered with my hair, I realized that it was time to shave my head: milestone number one.

I’ve never shaved my head before, so it was kind of a shock at first. But then I realized that I look like about 5 percent of the guys out there who shave their heads voluntarily. I’m still getting used to it, but I think I’m going to like it. I guess I don’t really have a choice….

Actually, though I didn’t know it, because I’ve never had cancer treatment before, my first cancer milestone was not losing my hair. It was installing a “port” in my chest. This was a surgical procedure that, once completed, allowed my cancer team to both draw blood and infuse the toxic chemicals known as chemo without having to stick a needle in my arm every time I went in.

The first thing that happens when I show up at the hospital — after I give my name and birthdate — is that a nurse draws a blood sample. Several vials, actually. Once the vials are full and accurately labeled (she makes me read the label out loud), they are analyzed and the results are sent up electronically to the nurses on the third floor. (Elevators are now a part of my new life as a cancer patient. I ride elevators every Friday).

With the latest blood sample, they can compare the new panel with my previous samples to see how things are progressing. I’ve been encouraged by my numbers: my “tumor marker” has dropped from 25,000 to 6,500 over two months. The normal range is 57 (I look forward to reaching that milestone).

Another milestone that I absolutely did not see coming was when I was standing in line to pick up my prescription of Creon, a digestive enzyme that my pancreas no longer produces, and without which I cannot digest many foods. As I approached the counter, the cashier looked at me, turned around and walked back to the shelves and reached for a white bag of… Creon.

She knew me from the many times I’d been to the pharmacy to pick up my prescriptions. I guess I could have felt flattered that I was recognized, but I felt more like, sheesh! I never saw any of this coming! Not the digestion issues, not the muscle weakness, not the weight loss and not being recognized by the folks at the pharmacy.

We all pass milestones, some welcome and others not so. Marriage? Happy milestone. Divorce? Not so. Moving into a new house in a new town is a big one. As we age, we pass many simple milestones like, well, now I need glasses. A knee replacement. A pacemaker. Or I can no longer … (fill in the blank).

For me, it was cancer.

Not having ever gone through this before, I hesitate to anticipate any future milestones. My cancer team always asks me the same questions when I go in for chemo: Have I fallen? Am I afraid of falling? Have I experienced nausea and vomiting? So far I’ve said no to all of these questions. But maybe there’s a milestone in my future where I begin to say yes.

Though receiving a chemo treatment can cause some side effects, it’s actually quite relaxing — except when I see the nurse don a protective gown and extra latex gloves just to carry the bag of toxic chemicals over to the tall wire stand where she hangs it so it can be pumped into my body. Once the tubes are connected, she peels off the gloves and gown and tosses them into the hazardous waste bin. She is very careful not to get even one tiny drop of this highly toxic drug on her skin.

Me? I’m taking it intravenously!

Everyone at the hospital is so kind and compassionate and helpful. They ask if I need anything like food (there’s actually a small menu), something to drink, or the TV remote. Sometimes I pass the time watching a nature program, but mostly I read or talk with friends on the phone, though since the chemo chairs are only separated by a thin curtain, there’s no sound privacy.

So I sit there for two hours while this toxic cocktail drips into my body through my port, counting the minutes until I can leave. Every time I go in — that’s three Fridays in a row and then one week off — I’m ushered into a different “room.” I ask for some hot oatmeal and cottage cheese and then wait until the pharmacy has prepared my chemo bag.

Once the pump has emptied the clear liquid from the clear plastic bag, the nurse unhooks the tube from my port, sticks a band-aid on the little hole in my skin, and says, ‘Okay, you’re free to go.” Yay! I head to the elevators, ride down to the parking garage and pay the $4 fee, then hop on I-5 South and back to the ferry.

I feel fortunate that I have a medical priority loading pass because after a day of chemo, I would find it difficult to sit in the car for an hour or more waiting for the next boat. I remember when I took my friend Ron over to get his cancer treatments and how nice it was to load onto the ferry first and to get him home. It feels so compassionate to me and I realize that even the Washington State Ferries has a heart.

Being aware of both past and future milestones may bring us some insight, but I don’t know if it can help us to avoid the ones we dread, like death. For all of us, there are milestones ahead. Children leaving home, grandchildren brought into the world, and parents dying.

So as time passes, I will look for more milestones in my life. Complete and total remission comes to mind. I think that all cancer patients hold out hope that they will be the outliers, the ones that beat the odds and actually survive. Steve Jobs had the same kind of cancer that I have but, even with his vast resources, after fighting for years, he finally succumbed. His final milestone was, like for many, a headstone.

Scott Durkee is a freelance factotum, artist and winemaker. He lives on Maury Island.