Have you ever watched a child die from measles? I have.

My family knows pandemics. During COVID’s first months, my sister, an emergency room nurse, transferred from Boise to Maimonides Hospital in New York City. The ER overflowed with patients struggling to breathe, the ICU was full, and dialysis machines and ventilators keeping patients alive clogged hallways. Ambulances transporting “COVIDs” lined up in front, and refrigerator trucks stacked with body bags lined up out back.

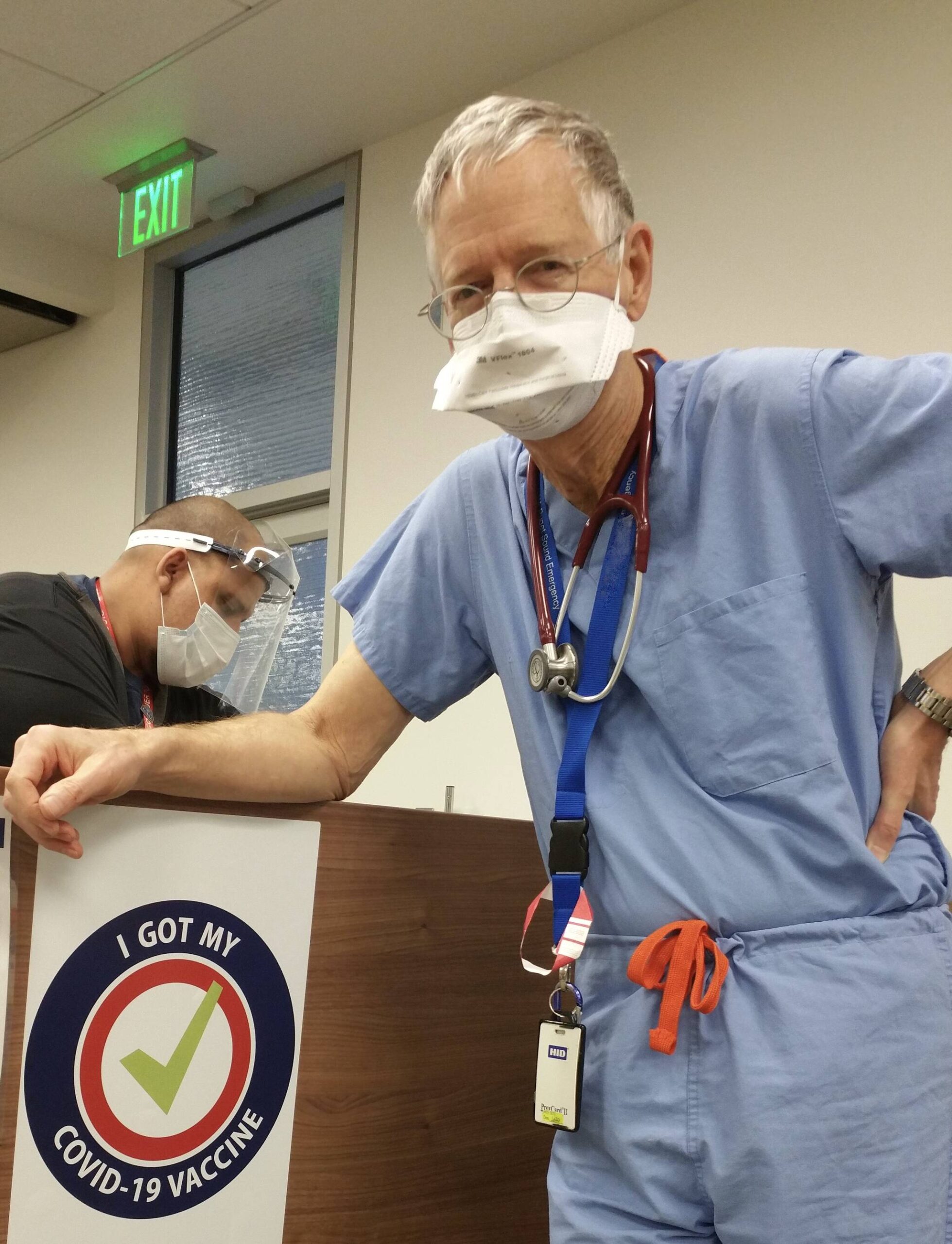

Now, thankfully, an ever-improving vaccine against COVID is available.

My mother, the first licensed nurse practitioner in the U.S., knew polio. After high school in Muncie, Indiana, she worked as a nurse’s aide caring for polio patients at Ball Memorial Hospital. That summer, 1949, fear was rampant. Mom slept on the porch to avoid exposing her family to the polio virus. Hospital wards were crammed, including with patients in iron lungs. Today, a highly effective vaccine against polio has virtually exterminated the disease.

Before flu vaccines, the influenza pandemic of 1918 killed millions, including a surprising number of young adults. One such person was my great-grandfather in Kentucky, who left behind eight children. My great-grandmother lost the family farm, driving the family into poverty years before the Great Depression.

Now, flu vaccines are updated annually to address ever-evolving virus strains. Even so, hospitalizations and deaths due to influenza remain significant in the United States.

Vaccines are vitally important locally and globally. As a doctor, I trained in mission hospitals in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and Lugulu, Kenya. In Thailand, where clinics served the Hmong hill people, part of our work was vaccinating vulnerable villagers to prevent measles, mumps, rubella, and tetanus.

In rural Kenya, our crowded hospital ward was filled: nearly everyone had malaria. One patient stood out. I’ll never forget that two-year-old girl struggling to breathe. She died from measles, a vaccine-preventable death. In contrast to measles, controlling malaria has proven difficult, but in 2021 a vaccine for children became available.

In 1981, the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, issued by the federal Centers for Disease Control or CDC, reported the first cases of young men with rare infections, some dying. Thus commenced the HIV/AIDS pandemic that swept the global community, killing more than 40 million people to date.

For 25 years, I directed an HIV/AIDS program. Thankfully, medications have transformed HIV into a chronic and treatable infection. At the Veterans Administration, the dangers of HIV/AIDS prompted a bipartisan Congress and the VA’s Infectious Disease team to establish HIV screening for veterans as standard practice.

Most recently, preventive vaccines are now in trials in African countries where AIDS still kills women and children at horrific rates.

Microbes will always come for us, exploiting our vulnerabilities. Pandemics throughout human history illustrate the astronomical costs, both financial and human, with millions of lives lost. When it comes to infectious diseases, we cannot let down our guard. Our health and science institutions must be supported for their essential public health work. And because pandemics arrive on commercial jets, we cannot go it alone: U.S. collaboration with global medical and scientific communities is imperative. “No man is an island …”

What can you do in this time of vaccine skeptics and conspiracy peddlers risking our communities with disease and death?

• Keep up on your vaccinations and encourage friends and family.

• Healthcare workers: volunteer with your local Medical Reserve Corps (MRC).

• Contact Congress: we need funding and vigilance for HHS, Medicaid, Medicare, and VA.

• Get your health news from trusted and responsible reporters.

In this age of anything-goes unregulated social media when “lies spread across the world while truth is putting on its shoes,” we must rise to the challenge of building immunologic resistance to our microbial adversaries.

John Osborn is a physician who volunteers with the Vashon MRC. He is co-author of “Moving Mountains: Creating the Nurse Practitioner and rural EMS” (2025).