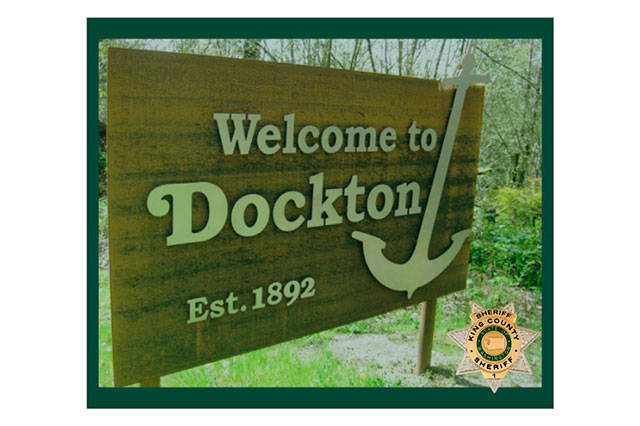

Longtime islander Kelly Robinson said he doesn’t know what would compel anyone to target a heavy, stainless steel sign welcoming visitors to Dockton.

But last week, culprits sawed through eight half-inch steel lugs fastening the sign to its posts on the side of Dockton Road and stole it. The sign was erected in recognition of the importance of Dockton’s cultural and historic heritage in 2010 as part of the Dockton Historic Trail project, funded by county grants and private donations. Robinson, who helped envision the half-mile loop through town along with his partner Anita Halstead and a group of determined Dockton residents, said the sign can be replaced. But he is feeling discouraged.

“It’s just amazing [someone would do this],” he said, adding that the sign is greatly admired. “We love this sign and we know that many of you love it.”

The original welcome sign cost about $4,000 to manufacture according to records, Robinson said, noting that there is a small amount of money left over from the project that could be used to help replace the sign. Along the trail are nine other information signs that tell the stories of Dockton’s past, from its shipbuilding days — Dockton was once home to one of the largest dry docks on the west coast — to the lives of the immigrants who labored and settled there. The trail also includes a commemorative bell and obelisk monument tiled with sea glass that washed up on island beaches.

The original welcome sign was designed by islander Richard Farner and crafted by Bob Powell of Metal Creature using a water jet cutter. Robinson noted that the plans to build the sign are still available, so any effort to recreate it would not need to start from scratch.

Scott Snyder, a maintenance coordinator who manages Dockton Park for King County, worked with the group who organized and led the trail project in 2010. He said the sign was a unique piece of artwork that required many hours to manufacture and added that nothing on the trail has ever been seriously vandalized before.

“It’s kind of interesting. You expect a certain level of vandalism; things get tagged, spray-painted occasionally, something small gets broken. But something like this, it’s pretty rare,” he said.

Snyder said that he hopes the original sign may be recovered. But if it is gone for good, he said, he would like to help figure out what it will take to replace it.

“It’s a very tragic loss,” he said. “This really was an unfortunate surprise. [This] just doesn’t happen.”