As the island’s patchwork of water systems ages and deteriorates faster than it can be replaced, rates for customers across Vashon have increased to account for basic infrastructure upgrades. But other pressures on several of the island’s water service providers are starting to mount.

As facilities require increasingly expensive maintenance and the longtime managers of the island’s water systems consider their retirements, what happens if the community loses local control of one of its most vital resources?

Gold Beach Water Company

Last year, two major utilities put out a call to private water companies on Vashon-Maury Island, making offers to purchase them. Two answered back.

In 2018, the Gold Beach Water Company and Burton Water Company entertained offers from Washington Water Service, a subsidiary of the California Water Service Group headquartered in Gig Harbor, as well as Portland-based NW Natural, though neither company went through with a final sale. But the door is open to potential deals in the future.

Compared to the mainland, where drinking water comes from several river watersheds, the island’s drinking water is sourced from aquifers that replenish annually with rainfall. King County has regulations to protect aquifers in unincorporated areas from contamination or depletion, earning Vashon the designation of a “critical aquifer recharge area.”

That recharge — water from rainfall or snow melt, for example — reaches the underground water table and replenishes the aquifers. In the boundaries of a critical aquifer recharge area, county codes implement several protections for water. They restrict development from encroaching onto sensitive areas and ban the use of certain materials such as asphalt millings, a byproduct of grinding up old pavement that was at the center of a controversy last summer over their deployment across the island to resurface driveways.

The county’s safeguards are meant to keep the island’s water the same as the Spano family found it decades ago.

Mike Spano inherited the Gold Beach Water Company from his father, who drilled two wells and assembled the original water system himself in the neighborhood that is home to 200 or so full-time residents today. Spano believes that his wells are among the most pristine on the island. But as the years have gone by it came time to decide what to do with them next.

Last year, Spano approached the Gold Beach community with an offer to buy the system, transferring control of its operation to the residents. The new arrangement would have left it resembling other household water cooperatives in neighborhoods scattered across Vashon. Spano laid out costs and benefits over two public meetings and made a case. But his offer was turned down.

“When it got down to nuts and bolts they were afraid there would be too much liability or something,” said Spano, adding that the system is in good shape and that his skeptics did not look at the situation impartially. “Nobody wanted to do the work.”

According to Steve Reed, interim manager of the water company, there were not many who felt moved to provide input one way or another.

“In two meetings on the subject less than 60 people showed up,” he said. “That’s not a quorum even if everybody voted on it.”

Reed said that residents could have purchased connections for around $1,600.

“Gold Beach would’ve been a hell of a buy, but it won’t be let go as inexpensively as of now because there’s going to be a lot of money put into it,” he said.

The Gold Beach Water Company currently charges a modest rate for water service at $32 a month per connection. It amounts to “paying hand to foot to keep things going” according to Spano, with a number of improvements now planned to update the old system and the connections it serves. Rates for customers will soon climb higher than they have in the past to help pay for the work.

Before any rate increase is put into effect, however, it will have to be approved by the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission, an agency that regulates the rates and services of 53 private water utilities in the state. The law requires that any rate hike be reasonable enough for customers to afford while remaining high enough to yield the company a return on its investment for tasks such as replacing old pipes or upgrading treatment equipment.

Jar Lyons, board president of the Gold Beach Community Club, characterized the vote against buying the water company as a “hot button item that everyone wanted to participate in,” motivated in part by concerns that the neighborhood would be taking on too much if it proceeded with the deal.

“A successfully run, locally owned water system is … 100% a function of who you get to do the actual work. If you can hire someone who’s good, everything’s fine, and if you can’t, it can be pure hell,” he said.

A certified operator is required to oversee water systems that serve more than 15 customers. They must be available to respond to emergencies such as outages, main breaks, system distribution or water quality problems as well as to conduct the necessary sampling set by the state Department of Health. Then there is the matter of general upkeep.

The determination made was that it would be better if the UTC were the agency to draw the line and protect residents from paying more money when things break down. He added that little to no funds had previously been set aside to complete capital projects for the water system.

“There were a lot of people who joined a task force to look at the financial numbers and get a sense of what the state of affairs was in the infrastructure. We took it very seriously and we spent a lot of summer weekends investigating this,” he said. “Personally I vacillated twice on my vote.”

Lyons said there were other reasons to oppose a deal to inherit the system. According to Lyons, there have been instances when the neighborhood has gone without water for a day with no word about when it will be back on. The lack of communication about service restoration, he said, has been offset by the neighborhood’s volunteer emergency response organization, keeping people up to date about what is going on when the news is available.

“You certainly won’t get any information from the company,” he said. “When things go poorly there’s nobody to answer the phone.”

Lyons said he isn’t sure whether a bigger entity would handle mishaps and service disruptions any better.

“For some water systems it could be a good thing getting picked up, and for others, it could be a bad thing,” he said.

Not long after Lyons and his neighbors rejected the proposal to buy their water provider, Washington Water Service dropped a line to the Gold Beach Water Company. Spano said they made him an offer — he was not at liberty to say for how much because he signed a nondisclosure agreement.

“In the future, something might come with them. There were a couple of meetings, a couple of calls from other interested parties, but nothing was brought to fruition,” Spano said.

Burton Water Company

Washington Water Service is not the only major utility with its sights on the island’s water. Margaret Wessel, the general manager of Heights Water — the island’s second-largest purveyor of drinking water — said she received a letter in the mail in August of 2018 from NW Natural about potentially selling the company to them.

“They were just fishing for interest,” she said, adding that the office has received other memos like it occasionally. “Of course we would never consider doing that.”

That’s because, in Wessel’s opinion, proper water management is done at the local level.

“Anytime water goes corporate, you run the risk of somebody deciding that its a for-profit industry and making a killing on it because it’s a necessary thing,” she said.

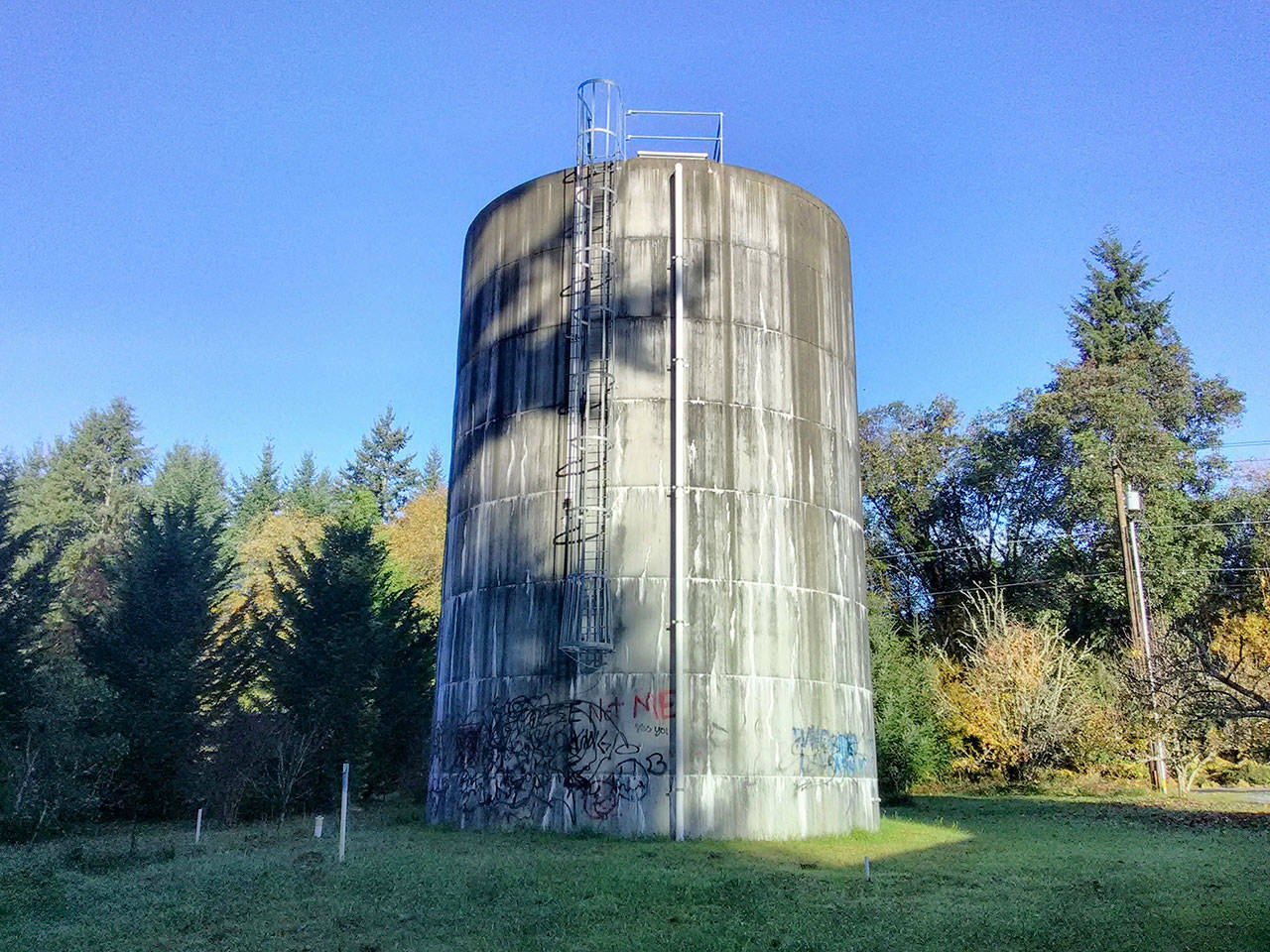

NW Natural has been busily expanding its reach, acquiring water service companies as recently as last month, from wastewater utilities in Kittitas County to a new holding as far away as Texas. Outside of town facing the Misty Isle Farm property, a 40-foot tall water tank towers over the houses on a residential street on a property where Jim Garrison and Evan Simmons, the owners of the Burton Water Company, are planning to drill new wells. NW Natural and Washington Water Service have both made offers to purchase the business, which serves about 400 connections for $34 a month, but Garrison said he was hesitant from the start.

“We were exploring the possibility and the two companies gave us prices, and then we kind of lost interest because this idea of selling it to a corporation did not sit too well with either one of us,” he said.

Both offers were made on the condition that Garrison and Simmons sign nondisclosure agreements, which they did. But Garrison said they would prefer another outcome.

Simmons’ son, Nick, who has an engineering background, has assisted on daunting projects and helped perform major repairs for the company. Garrison is hoping he might take over someday.

“It would be better for the whole community,” he said.

Whether or not that happens, Garrison said he has an idea of what the larger utilities are interested in. He believes that corporations with deep pockets see an opportunity to sink their excess cash into water utility enterprises such as those on the island, setting themselves up to enjoy a generous rate of return on the investments they make in them.

Evan Simmons agreed, adding that they appraise companies such as Burton Water based on the revenue that can be generated through rates. He noted that years of investing their own profits into both minor and serious infrastructure needs at the Burton Water Company has led to the business accumulating value over time.

“Overall, I feel like the system is in decent shape. It really should be measured, I think, by whether the water is clean and reliable and relatively inexpensive. Those are the three markers. And I think it’s pretty good.”

So does Nick Simmons, who said he is most interested in finding solutions for the water system to work better. On a sunny afternoon last week, he was standing in front of a 30,000-gallon in-ground concrete tank explaining how the water they distribute is chlorinated to kill disease-causing pathogens, diluted to a precise, measured dose based on demand.

“It is a legacy system. There was a lot of stuff that was done in the 50s, 60s, and 70s that is not done in the way that it’s done today,” he said. “Figuring out sort of how to solve the problems as they occur and figuring out ways to fix the system is really interesting. It’s like a big puzzle.”

Simmons doesn’t know if he will step into the same role as his father at the Burton Water Company someday. But whoever does, he said, needs to appreciate that the purpose of their job is to connect islanders with fresh, clean water — and to protect it for the future.

“A lot of people don’t think about water. They turn the tap on and that’s as far as it goes.”