By Andy James

For The Beachcomber

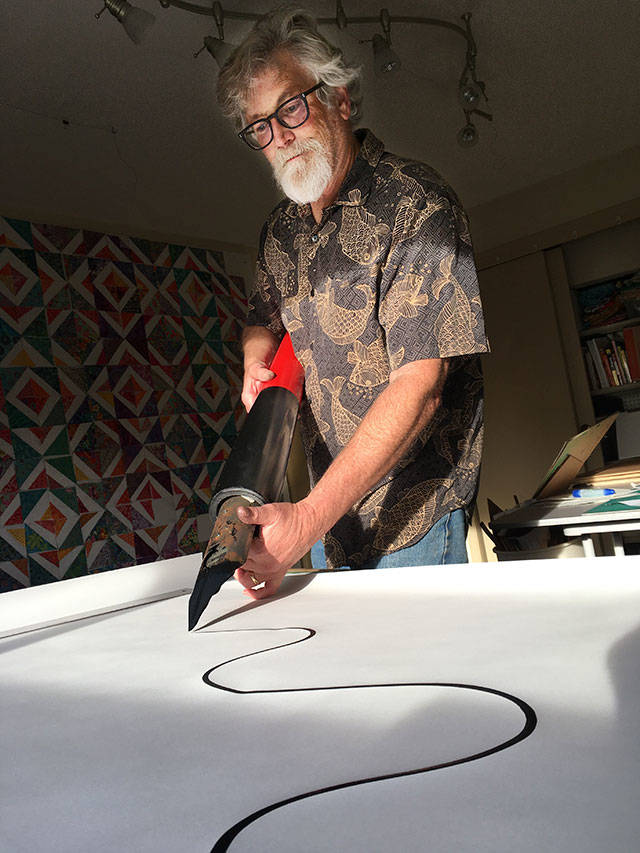

Editor’s note: This is the first in The Tools of the Trade, a series of articles about the tools that islanders rely on for their work. This week, renowned graphic artist Jim Woodring talks about the giant steep dip pen he created for making large-scale drawings.

Jim Woodring’s giant pen came from a dare only he was aware of.

The Vashon cartoonist was visiting a London vendor of pen-points when he remarked on an oversized nib — the business end of an old-fashioned ink pen — a few inches long.

“He goes, ‘oh yes, you couldn’t make them any bigger than that, they just wouldn’t work,’” Woodring said, quoting the vendor. “And, you know, that kind of got my colonial ire up. I thought, ‘well, no Limey’s going to tell me what I can and can’t do.’”

With decades of surreal invention under his belt, Woodring created an ink pen as big as he dreamed it: Shoulder height when standing, with a nib to scale.

“I visualized how it would work by having those nesting plates in there to hold the ink and control the flow through capillary action or surface tension,” he said. “It worked like a charm from the first outing; it was great.

Woodring said other people have made giant pens that just don’t seem to be able to write.

“This is the first real drawing tool of its kind,” Woodring said.

He discovered he had created a kinetic play-thing that fueled new modes of expression.

“It’s like your whole body becomes your hand. It’s like your arms are your fingers,” Woodring said. “It doesn’t weight that much. The inkwell is a vase.”

As got used to using it, he thought to himself, “this pen makes some actually pretty sensuous lines.”

“You could have shape and form and vibration with this pen in a way that you couldn’t do any other way,” Woodring said.

Woodring displayed a few of the oversized ink drawings, alongside the pen he used to create them, at Valise Gallery on Vashon in 2016. A larger collection of 30 works followed at Seattle’s Frye Art Museum in 2017.

Woodring’s artwork and comics depict a surreal, fluid world, often taken directly from his dreams. The hallmark of these visions is a meticulous texture of finely-drawn lines.

Woodring remains devoted to inking with steel dip pens, which have mostly faded from use with the rise of felt pens. Woodring keeps thousands of nibs neatly ordered in his studio, along with the tools and patience to maintain them.

He said using such pens is a throwback to what people centuries ago would use to write with.

“I like the idea that when you are [using a steel pen] you’re dealing with the exact same situation as the people who used steel dip pens. [Albrecht] Dürer [a German painter and printmaker] used a steel pen — the exact same thing,” Woodring said. “It’s hard to be in touch with that antique technology any more, you know.”

Even the pitfalls of steel nibs make Woodring love them all the more.

“When you sit down with a bottle of ink and a pen, and you’re trying to ink a drawing, somewhere in that drawing, there’s going to be a mistake,” he said. “It’s just the way that it is. And that adds to the beauty of the thing as far as I’m concerned.”

Woodring values the chance to go from his minuscule ink drawings to the drafting table where he puts the giant pen to use.

“Working on that scale, the fun of walking around the table and everything, it’s really enjoyable to do those things,” he said.

Woodring said the outcome of his drawings would be different were it not for his giant pen.

“If you’d done one of those big drawings with a brush or any other tool, the line would have been different,” he said. “There’s just something about the compass-like precision that you need to carve those lines with that thing and the way it automatically makes thick and thin as you move.”