During the late 1980s and early 1990s, a dramatic increase in ferry auto capacity came to Vashon-Maury Island largely unannounced. At the time, there was little recognition of the impact this “ferry revolution” would make and how irrevocably Vashon-Maury Island would change because of it. These increases led to a gentrification of the island brought about by urban professionals, retirees and increased wealth. With the uncertainty of the commute largely eliminated, the increase in technological commuting and the increased congestion of regional traffic as area infrastructure improvements lagged behind growth, it was now as easy to get to mainland jobs from Vashon as it was to get to them from Duvall, Issaquah or Auburn.

As the Seattle economy boomed in the 1980s and 1990s, and Seattle housing costs soared, Vashon-Maury became a rural haven in a rapidly expanding urban sprawl that engulfed more rural mainland areas such as Marysville, North Bend and Covington.

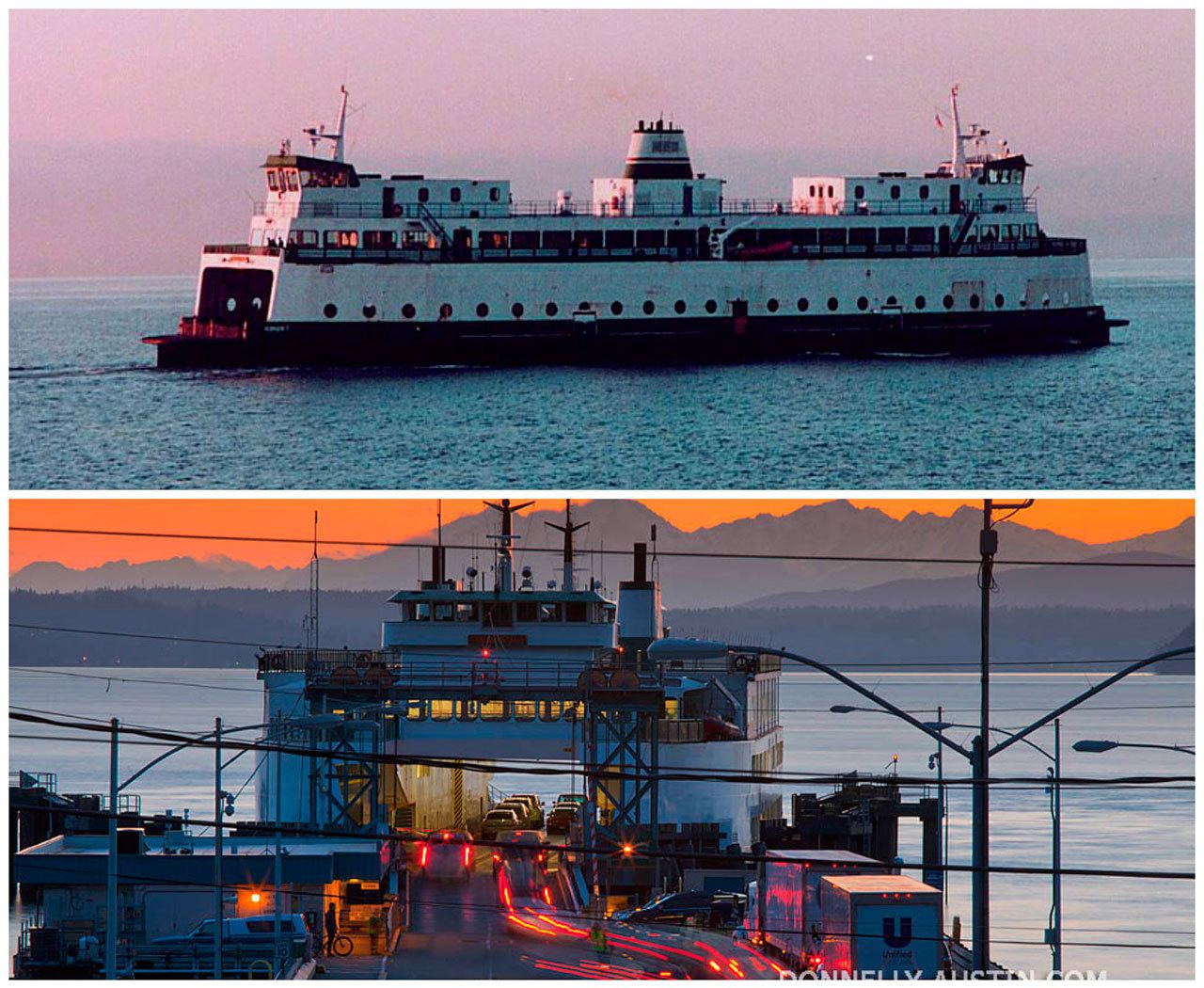

Well into the 1970s, the north-end dock was served by two steel electric ferries, the 59-auto capacity Quinault and Klahanie, and by the 87-auto capacity Evergreen State Class Klahowya, for a total capacity of 205 autos and 2,002 passengers.

With the removal of the steel electric ferries and the launching of the initially trouble-plagued Issaquah-class ferries, capacities began to change. By the mid-1980s, Vashon’s north-end dock was served by two 87-auto capacity Evergreen State Class ferries, the Klahowya and Tillicum, and the 124-auto capacity Issaquah, for a total capacity of 298 autos and 3,092 passengers. This 31 percent increase in automobile capacity and 54 percent increase in passenger capacity was expanded even more when, in 1990, the 230-passenger-only ferry Skagit was added with a Vashon-downtown Seattle route, bringing the total increase in passenger capacity to a whopping 66 percent.

This ferry revolution, which took place in less than a decade, dramatically changed the north-end commute to Vashon. Expanding the impact of this increased ferry capacity at the north end was Metro Transit’s co-ordination of bus routes with the ferries. Buses from the island rode ferries to Fauntleroy, and multiple buses met arriving ferries at Fauntleroy. This increased bus service worked with the increased capacities of the ferries to boost commuter ridership even further.

The net effect of this mini-transportation revolution was to make Vashon much more accessible to commuters and led to a dramatic 26 percent population growth during the 1980s compared to the 13 percent population growth during the decade of the 1970s.

As the Puget Sound basin emerged from the economic recession of the 1970s, and, as transportation access increased dramatically, Vashon felt the impact as more and more people sought to live the rural-suburban lifestyle of the island.

Vashon-Maury Island became another “gated community” in a rapidly expanding upper middle class land rush in the Puget Sound region, with the ferry system providing the gates. Retirees and individuals with significant wealth (some times both together) “discovered” Vashon and began a gentrification of the island that many think began to turn Vashon into a “Martha’s Vineyard West.”

— Bruce Haulman is a Vashon historian, and Terry Donnelly is a Vashon photographer.