A new report from the Washington Poison Center shows that there has been an increase of calls regarding potentially dangerous exposures to hand sanitizer, bleach, rubbing alcohol, and other household cleaners at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

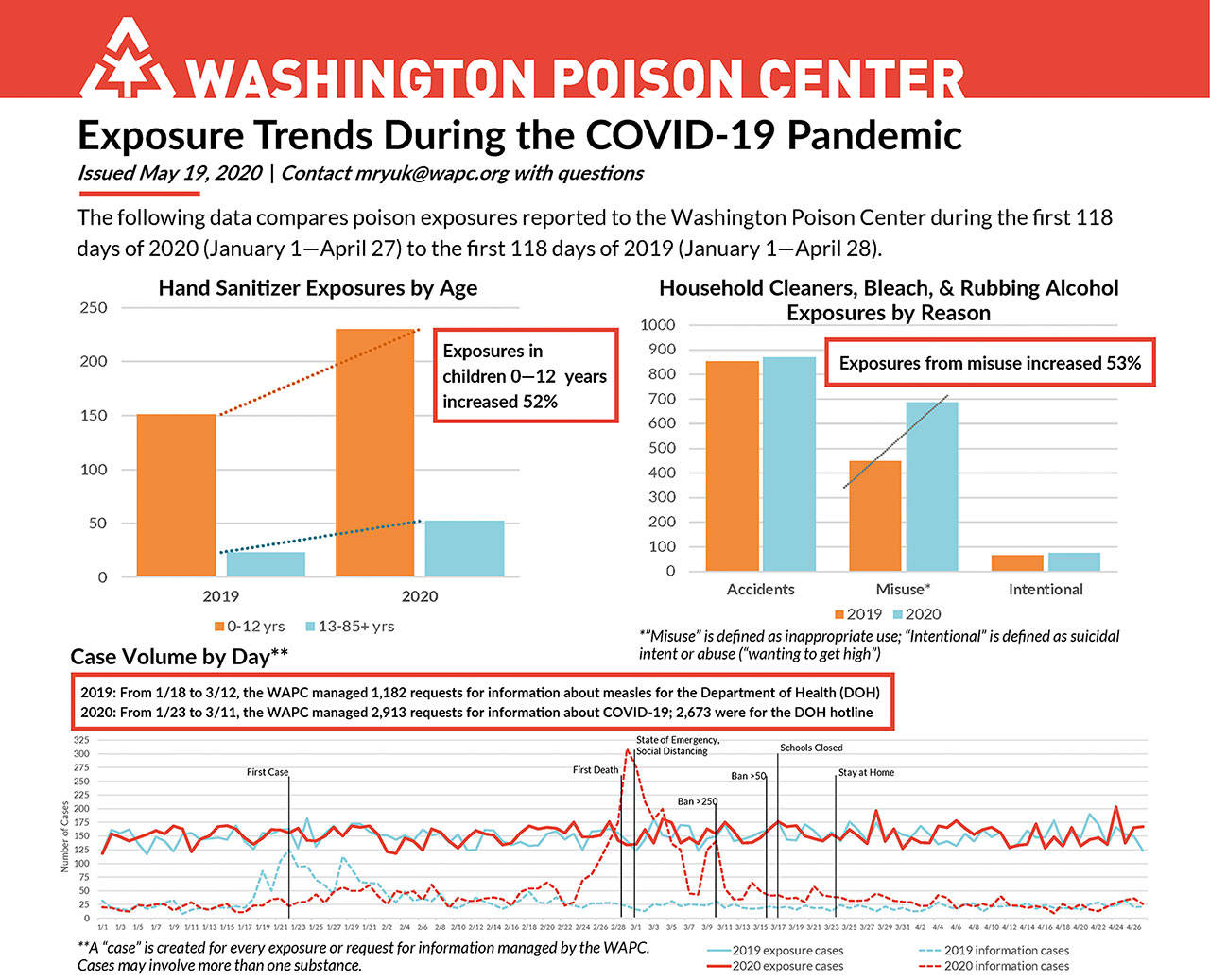

According to the report, published May 19, there was a 52 percent increase in the number of calls made to the poison center regarding children ages 0 to 12 being exposed to hand sanitizer between Jan. 1 and April 27.

Additionally, it appears there was a 53 percent increase in the number of incidents where cleaning agents were being “misused.”

But before any conclusions are jumped to, it should be noted that “exposures” to chemicals and chemicals being “misused” doesn’t always mean that someone was poisoned.

An exposure is “any suspected or actual contact with a substance which has been ingested, inhaled, absorbed, or injected into the body regardless of toxicity or clinical manifestation,” said Dr. Erica Liebelt, medical director of the Poison Center.

Liebelt gave the example of a mother sanitizing her child’s hands before eating, and the child rubs their eyes.

Even if the child was showing no symptoms, “If mom called us… to make sure she wouldn’t have to worry about anything… we code that as an exposure call,” Liebelt said. “We also look at outcomes, and we would code ‘no effect’” for this particular example.

“A poisoning… is when an exposure results in an adverse reaction,” she continued, expanding on her example of the mother and child — if the child starts to cry or say they’re in pain, that would be coded as a minor poisoning.

“Misuse” of chemicals is also a term that trips some people up, Liebelt said — it means using the chemicals in an incorrect manner (like mixing chemicals or not diluting), rather than abusing chemicals in order to get high (that’s classified as an “intentional” exposure).

“I’ll give you a great example — [mixing] bleach with the ammonia in the toilet. So common,” she continued. “All of a sudden, they start having difficulty breathing because there’s a gas emitted called chloramine gas.”

Some of the calls that went to the Poison Center involved exposures that were common before COVID-19, like the bleach/ammonia situation, Liebelt said. But others are specifically related to the coronavirus.

“People are taking spray disinfectants and spraying their homemade cloth masks with it. Then they put the cloth mask on their face and they start inhaling the fumes. Or, they’re soaking their masks in bleach to clean them,” Liebelt said. “Public Health recommends washing your masks with soap and water.”

Liebelt stressed that the Poison Center did not receive any calls that may have been related to President Donald Trump’s April 24 statement of using disinfectants “by injection” to kill the coronavirus.

The Poison Center report also detailed how many calls it was taking during the pandemic’s earliest moments.

It appears the Poison Center started to receive marginally more calls after Jan. 22, which was when the state supposedly discovered the first case of COVID-19 in Washington.

However, calls spiked from between 25 and 75 calls a day to more than 300 days before the first death was reported on Feb. 28, and continued to be high for several more days after Gov. Jay Inslee declared a state of emergency on March 1.

Another spike in calls, which tripled from 50 per day to about 150, happened when Inslee’s first announced his ban on gatherings of more than 250 people on March 10.

It appears call volumes returned to normal from March 15 until April 27, the end date of the report.