Over the Christmas holidays, Islanders who ride the passenger-only boat from Vashon to downtown Seattle showered the crew with cookies, cards, even hand-knitted hats — tokens of gratitude for a crew and service many commuters have grown to appreciate.

Indeed, since King County took over operation of the so-called PO boat last fall, this one-of-a-kind commute has only gotten better, many of those who use it say. The catamaran that the county leases is faster and quieter than the boat Washington State Ferries used on the route. The seats are more comfortable. And with two extra runs a day, commuters have more choices.

“Just about everyone I know who takes the PO has seen a huge improvement with management now under King County,” said Islander Kristin Thompson, who helped to organize December’s “appreciation event.” She and others spearheaded the effort, she added, because “we were all so blown away by the improvement.”

By nearly every measure, the service seems to be in better shape.

Ridership, for instance, has climbed significantly since King County took over the service last October, with the greatest growth reflected in the latest numbers: Between January and May, ridership was nearly 36 percent higher than over the same period a year ago.

So popular is the boat that the 5:30 p.m. sailing from Seattle to Vashon is sometimes over-subscribed. On more than one occasion, the King County boat has reached its Coast Guard-mandated capacity of 150 — and Islanders were turned away.

Hank Myers, who took over as head of the King County Ferry District three months ago, said he’s pleased by how the service has worked on Vashon — a run he calls “logistically simple.”

“I have to say, Vashon has been remarkably easy to deal with,” he said last week.

But the county’s new service is not without its problems. Financially, the service is precarious, and administrators are dipping into its reserves at a rapid clip. And while the Vashon run has gone smoothly, the ferry district’s other route — the West Seattle water taxi — has become a political target by conservative pundits who see it as a glaring example of government waste.

As a result, some say, the ferry district remains politically vulnerable in the county’s fiscally tough environment, in large part because boats — mile for mile — are an expensive way to transport people.

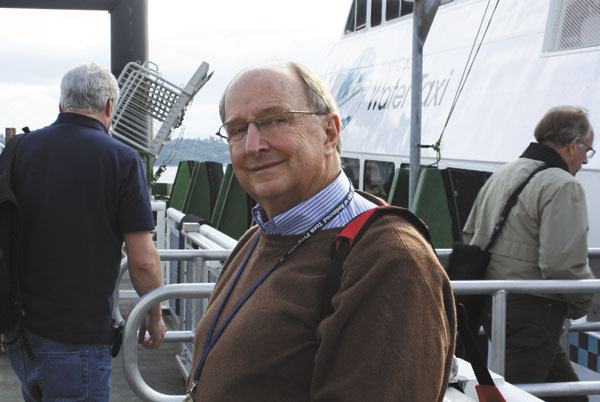

Myers, 65, a longtime transportation consultant and civic player who moves easily through the world of politics, said he understands the dichotomy the service is facing.

“The people who use it like it,” he said. “The people who don’t use it don’t like it.”

The county agreed to create a ferry district and take on operation of the region’s only year-round pedestrian boat three years ago, after the Legislature decided the state needed to get out of the costly passenger-only service.

Some in the county were excited about the prospects of a ferry district and saw it as an opportunity to build a regional waterborne transit system.

Led by then-County Councilmember Dow Constant-ine, the council approved a property tax of 5.5 cents per $1,000 of assessed value, directing the money towards the development of several additional runs — connecting, for instance, Kirkland with the University District.

Then the county got slammed by one of its biggest budget crises in decades. And in an effort to salvage a financially strapped Metro transit system, the proposed additional routes were scrapped, and the lion’s share of those property tax revenues was redirected to Metro.

The ferry district was not entirely dismantled, however, and the Vashon and West Seattle runs were maintained. But Myers said the county’s funding decision — redirecting 94 percent of the ferry district’s budget to Metro — has created a financial crisis for the small ferry system.

As a result, he said, the ferry district is dipping into its reserves to the tune of $6 million a year to keep the current system afloat.

“We’re on a non-sustainable model right now, which we’re trying to resolve,” Myers said. “We know we have enough reserves to go for another couple of years, based on our current expenses and current revenues. But we have to increase revenue and reduce expenses, or convince the council that cutting our budget by 94 percent was way too much.”

Myers, who has a background in the airline industry, said he’s working on a marketing plan that he hopes will increase ridership on the West Seattle water taxi. The county also has funds in place to purchase new boats, which will be tailor-made for the ferry district and will reduce operational costs even more.

Last week, as he sailed across the Sound on the Vashon-Seattle run — a ride he took so as to discuss the new ferry district with The Beachcomber — he said he’s optimistic the situation can be resolved. “I would not have taken the job if I didn’t think we could accomplish it,” he said.

Ironically, the Vashon route under county management is financially stronger than it was under the state, Myers said. Labor costs are down, since the county’s labor contracts are not as lucrative as those provided by the state ferry system, he said. Fuel costs, too, have fallen: The catamaran the county leases is far more fuel-efficient than the aging boat the state had used.

The county, in response to critics who questioned the ferry district’s expenses, produced an analysis of the monthly costs of the two runs last month. What they found was encouraging, Myers said: The county’s cost of operating the Vashon run fell $62,310 in April compared to the state’s costs for the service in April a year earlier.

The ferry district’s Achilles heel is the West Seattle route, which saw its monthly costs go up after the ferry district took on the run from Argosy, a private operator. But the Argosy run was subsidized by the county, Myers said, making the comparisons not completely accurate. What’s more, he said, the combined costs of the Vashon and West Seattle runs are less than the combined costs a year ago.

Myers, who also serves as a Redmond city councilman, said he knows that numbers alone won’t win the day. “We’ve got to face the fact that it’s a political issue as well as an economic one.”

Expansion of the ferry district may not be in the cards, Myers added. But he believes he can hold on to the status quo.

“As long as we can show some progress, I’m confident we’ll be able to maintain this level of service,” he said.

Those who depend on the boat say they’re hopeful Myers is right.

“I would be most unhappy if the PO boat went away,” said David Van Holde, a longtime commuter and an energy manager for the county.

Van Holde was recently turned away from a full boat — a situation he took in stride. He and a few others who also couldn’t board went to a bar, drank wine and caught the next sailing.

“It made me realize I shouldn’t wait until the last minute, and I don’t anymore,” he said.

David Bolin, another commuter, said he appreciates not only the comfort and convenience of the PO boat, but also the camaraderie.

Birthdays are routinely celebrated, he noted, and he too would hate to see the service cease.

“There’s a community on that boat,” he said.