An earthquake along the Cascadia Subduction Zone could bring tsunami waves of 10 feet or more to Quartermaster Harbor.

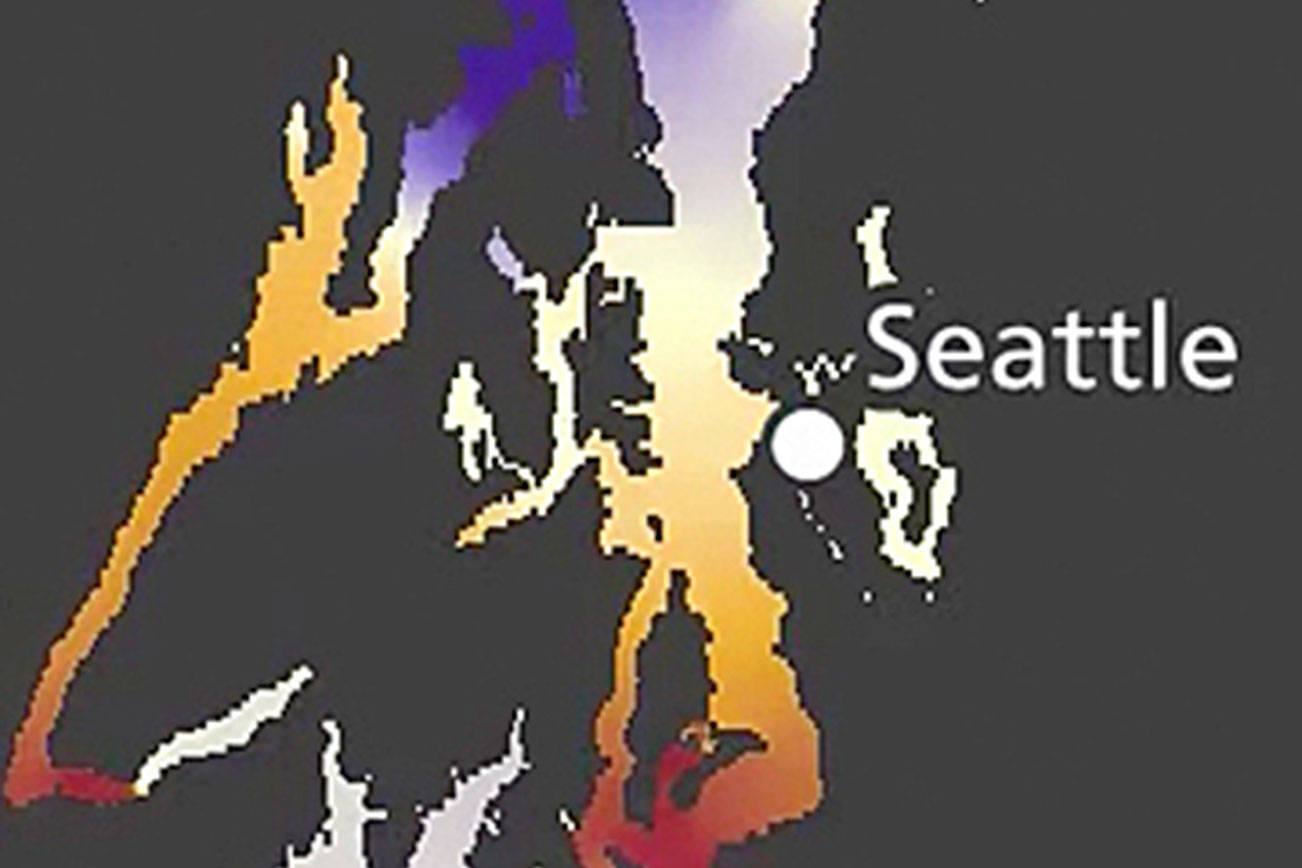

That information about Vashon’s tsunami risk is not new, but was illustrated in a series of videos the Washington State Department of Natural Resources released last week, showing wave simulations for the Washington coast and more detailed views for Bellingham and the San Juan Islands. The simulations show a tsunami after what is sometimes referred to as “the big one,” a 9.0 earthquake along the full length of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which stretches from northern California to northern Vancouver Island. While the videos do not focus in detail on Vashon and Maury Islands, some of the effects to the islands are evident in the simulation.

The first waves reach the outer coast in about 15 minutes. The tsunami then travels through the Strait of Juan de Fuca and into Puget Sound, reaching the Tacoma waterfront about two hours and 30 minutes after the earthquake. Along the way, the waves would hit the north portion of Vashon, then travel down the east and west passages on either side of the island, around the eastern edge of Maury Island, down to Commencement Bay, which is expected to be hit hard in this scenario. From there, about three hours after the quake, waves measuring potentially 10 feet or more would reflect back northward into Quartermaster Harbor.

“It gives you a big bear hug,” said Washington Geological Survey’s Daniel Eungard in a recent phone interview. “It wraps around both ends of the island and then moves back up to Quartermaster Harbor from the south.”

The two-minute video represents six hours in real time, with big waves washing in repeatedly to Quartermaster Harbor in the hours after the first wave. Eungard stressed that tsunamis are multiple-hour events, sometimes with high waves lasting 14 hours or more.

The videos are not meant to alarm, but to educate, with state officials and local disaster preparedness experts encouraging residents of the region to be prepared for earthquakes, including the full rupture of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, and resulting tsunamis.

“The community should start preparing — and I know they are in many ways — for when Cascadia happens,” Eungard said. “It is not if, but when.”

Along with having ample food, water, medicine and family disaster plans, Eungard said planning should include being ready to run to higher ground when an earthquake hits.

“The shaking of the earthquake is your warning,” he stressed.

He noted the duration of shaking is indicative of the quake’s severity. A quake of five to 10 seconds is likely minor, he said, while a quake of 30 seconds to a minute is major, and a quake of several minutes is likely a rupture of the Cascadia fault.

“Any amount of shaking should be your indication to get out of harm’s way,” he said.

That means people on low lying areas should move — on foot — to higher ground, and people in boats should move to deeper water or at least separate themselves from other vessels so they do not collide. Once safe, people can then check their phones or connect with emergency management to learn about the quake and determine if it is safe to return.

In tsunami areas, Eungard said, it is important to move quickly first — and then determine if heading to high ground had been necessary.

The simulation videos do not show how far inland the water would travel on land on Vashon and Maury Islands, but that modeling is in progress and is expected to be completed later this year. Eungard shared general information about that risk, noting that steep cliffs, of course, stop waves. But lower-sloping areas could allow the water to funnel up and reach higher levels than the height of the waves themselves, meaning a 10-foot wave could reach 12 to 18 feet inland. Potentially, Eungard said, this type of wave behavior could occur in Quartermaster Harbor.

Tsunami damage would come not just from high water, but low water as well. In fact, Eungard noted that in all the inland waters, what people would see first in a tsunami is the water receding, being sucked out of the bay and away from the shoreline.

“Before the peak arrives the trough would arrive first,” he added.

This action presents a major danger to the maritime community, including for ferries, shipping vessels and recreational boaters, with the possibility for grounding and vessels being unable to move before the wave comes.

Currently, Eungard said, Washington’s Emergency Management Division is working on a plan for the maritime community so that large entities, such as the Coast Guard, Washington State Ferries and the ports of Seattle and Tacoma all know what to do when a tsunami alert is issued.

On Vashon, Rick Wallace, the vice president of Vashon Be Prepared, said he is always pleased when new information, such as the videos, come out because the risk is real.

“It is clearly not true, like some people believe, that we are immune from tsunamis because we are protected here in Puget Sound,” he said.

He also cautioned that there is a risk connected to videos like those recently released: People can look at them and believe that portrayal is exactly what would happen. But he stressed there are multiple variables of what may occur, including where the earthquake was located: within the Cascadia fault — or in the Seattle Fault just to the north of Vashon or the Tacoma Fault, which crosses the island under Point Robinson. Earthquakes in both of those faults have generated tsunamis previously — and those tsunamis would affect the island in minutes, not hours.

“I personally worry more about a tsunami from those two faults, the Seattle Fault and the Tacoma Fault, because there would be no time for a warning in those situations,” he said.

He noted that the four-day Cascadia Rising drill in 2016, which was also based on a 9.0 earthquake along the Cascadia Subduction Zone, included a roughly 1 foot tsunami in Quartermaster Harbor — far less than depicted in the recent videos. But even that small of a wave could cause significant damage, including to marinas, he said, referencing the shaking of the quake and abrupt changes in water levels.

“What people have to understand is that it is so unpredictable that you can’t know what your damage will be to a house or bulkhead,” he said. “The important thing is that it places an emphasis on being prepared because it is so unpredictably dangerous.”

Like Eungard, he stressed the importance of leaving the low-lying areas in the case of a quake — and doing so on foot to avoid traffic jams and other obstacles.

“If I lived at the beach, and there was really severe shaking, I would run,” he said.

He also acknowledged Vashon’s vulnerability — and stressed islanders’ responsibility.

“As always, citizens are responsible for being resilient for themselves,” he said. “No matter how much you planned, and no matter how many resources you have … there is no way that everyone who would be affected by this could be taken care of. So people in their homes need to prepare themselves.”

On the island, Wallace said there is no mechanism to warn people that a tsunami is coming, but he said with enough notice, he is sure emergency and disaster responders would try. He also encouraged islanders to sign up for emergency alerts through the King County Office of Emergency Management.

Discussing the tsunami threat, Vashon Island Fire & Rescue Chief Charlie Krimmert said in such a scenario, life and death decisions would need to be made, and the destruction to the island would likely be enormous, compounded by possible damage to both ferry docks and island-wide power outages. A tsunami would be a regional event, he added, and emergency responders would not be streaming to the island to assist.

“The real speech is be aware of the circumstances and be prepared,” he said.