There’s little question but that James McCrackyn, a 7-year-old Island boy, loves dogs.

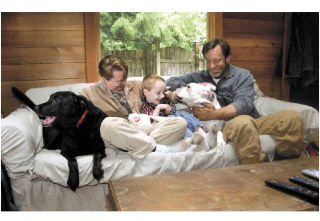

During a recent visit to the tiny home he shares with his parents, he sank into the couch next to Cleatus, an American bulldog, and Rosa, a black Lab, two animals bigger than he is, and laughed as they covered him with sloppy kisses.

Now, his parents hope a dog might change his life.

James, a boy with autism, has been preliminarily approved to receive a highly trained dog from Autistic Service Dogs of America. If his parents can come up with $13,500 by June 8, James and his parents will travel to the organization’s headquarters in Lake Oswego, Ore., next February, where James will be matched with a dog that meets his needs and personality.

Raven Pyle-McCrackyn and Mark Frey-McCrackyn believe such an animal could have a profound effect on their son, whose autism ranges from moderate to severe.

At home with his family, James seemed joyful and exuberant. He ran around the house, grinned at his parents and sometimes crashed playfully into his father’s strong chest. The family’s two big dogs romped with him.

But in other settings, James, a slight boy with a thatch of blondish-brown hair, easily gets overwhelmed and frightened. He might try to run away or shriek when he enters his classroom at Chautauqua Elementary School, Raven said. When he’s particularly anxious, his speech — already profoundly delayed — seems to disappear altogether.

A service dog — carefully raised from puppyhood to support an autistic child — would comfort James when he’s overwhelmed and rein him in when he tries to run away. The dog could also help James engage with the world, as the animal, who will accompany him everywhere, will undoubtedly draw people to the unlikely pair.

“His need for consistency is great, and the dog will help him with that,” Raven said. “No matter where James goes, he’ll always have that dog. If there’s a fire drill at school, he’ll have the dog. If he’s on an airplane, he’ll have the dog.”

When Raven and Mark told James’ neurologist that they wanted to get a service dog for their son, he strongly endorsed the idea.

“He thinks James is a perfect candidate,” Raven said. “James really likes dogs, and his anxiety really increases his autistic symptoms.”

As a result, the family is now trying to find the funds to make the dream a reality.

Thanks to the Maravilla School, a small, private school on the Island, fundraising boxes have appeared throughout the community asking Islanders to help in the family’s quest. Raven recently sent out an e-mail to some 30 friends, family and acquaintances, as well.

A down-to-earth woman, she seemed overwhelmed already by the response: In less than a week, the family has raised $5,000 towards their $13,500 goal.

“We’ve been crying a lot,” she said. “We get a note. We get a check. We get a letter. And we just burst into tears.”

Service dogs have been supporting people with disabilities for years. But the use of these highly trained animals — usually golden retrievers, Labrador retrievers and golden-Lab mixes — to assist people with autism is relatively new. Autism Service Dogs of America (ASDA), one of the few such organizations, was founded six years ago.

According to Raven and the ASDA Web site, these dogs help autistic children in large part by both comforting them and helping them become more socially engaged in the world. A nuzzle from the dog can help an emotional outburst to subside. The dog’s constant presence can strengthen the child’s sense of security.

They’re also trained to watch for seizures, something autistic children are susceptible to; and if a child tries to run away from an over-stimulating situation, the dog will herd him or her back into place, Raven said.

Because of the effect anxiety has on James’ autism, he takes a heavy dose of anti-anxiety medicine every day. “We hope we can wean him off of that if we have a dog,” his mother said.

The dogs cost so much because of the thousands of hours of training that go into each one. Indeed, each animal is worth more than $30,000 in staff and training time; grants and donations the organization has received helps to subsidize the costs of the dog.

The agency also supports each family with considerable staff time, Raven said. Next February, if the funds are raised and James gets final approval, he and his parents will travel to Oregon, where they’ll stay for two weeks while staff members match James with the right dog and train both of them about how best to use the animal.

Once James arrives back home, a staff member will come to Vashon for a week and again help the family fully incorporate the dog into their lives.

Raven and Mark had thought about a service dog for James for some time, especially in the last year or so, as James’ emotional outbursts grew more frequent.

“As things began getting more and more difficult for him, I started asking more and more people, ‘What do you think?’ And when I talked to our neurologist and he practically did a jig, I knew I should do this,” Raven said.

They briefly considered the idea of getting a puppy and working with ASDA to raise it into a service dog — an approach that ensures strong bonding — but Raven decided their needs were too great.

“We need help now,” she said.

Like most families with a disabled child, the McCrackyns have hugely altered their lives to support their son, a boy they clearly love dearly. He was 2 when he was diagnosed, a medical decree that spelled an end to a job Mark relished — working as a forester in Klickitat County, a sparsely populated part of the state with few services. The family was already living part-time on Vashon. Though it was hard for Mark to walk away from his job, they decided to make the Island their permanent home. He now works as a groundskeeper for the Vashon Island School District; Raven is a tax preparer on the Island.

Once on Vashon, they found a nanny, Krystal Strobel, who was perfect for James — calm as well as committed to helping him — and they paid for her to get specialized training to help her work most effectively with him. They’ve secured private speech therapy for James, supplementing the speech therapy and other specialized services he gets in his classroom at Chautauqua.

Most important, Raven said, they knew they had to do all they could to strengthen his bonds with them and keep him safe. So last fall, they moved from a spacious house to a 580-square-foot home — former missionary housing just down the road from Bethel Evangelical Free Church — so that they can see James at all times and stay as tight-knit as possible as a family. His bedroom, a tiny loft, looks down onto theirs.

Raven, who trained as a special education teacher before going into tax work, said she struggled mightily with the news that her son was autistic. She recalls “yelling at God,” as she put it, telling him, “I changed my mind; I now do taxes.”

Now, though, she sees her son as the perfect child she longed for. He’s affectionate and funny. If she needs a break, he can easily entertain himself. And he’s almost completely in the moment, she said.

“People spend a lot of money in therapy to live the way he’s living,” she said with a laugh. “He’s the best kid in the world.”