Editor’s Note: On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which resulted in 120,000 Japanese Americans being sent to internment camps, taking with them only what they could carry. Feb. 19 is now recognized as an annual Day of Remembrance.

Some 70 years after it happened, Mary Matsuda Gruenewald recalls the day her brother left Wyoming’s Heart Mountain War Relocation Center, a concentration camp for Japanese Americans, as one of the saddest times in her family’s life.

Her re-telling of that day is captured in a video for The Japanese Presence Project, an island initiative that aims to recognize the contributions of the Japanese-American community on Vashon and the losses its members endured.

As Gruenewald tells it, her brother, Yoneichi Matsuda, and other young men from the camp had joined the army and had boarded a bus that would take them away to serve in the war. Gruenewald, now 91, recalls how she and her parents went to the bus and — standing outside the window near his seat — said goodbye to him.

“Here we are crying, and he is crying and then the bus pulls off and away. I mean that scene is indelibly printed in my head of what it felt like to have Yoneichi go to fight for the United States that was holding us prisoners in these internment camps,” she said.

Many islanders know Gruenewald as the author of “Looking Like the Enemy,” her 2005 book about leaving her Vashon Island home as a teenager and being imprisoned in an internment camp during World War II, but this particular story was recorded just months ago and is available online as part of a research effort spearheaded by island historian Bruce Haulman and social demographer Alice Larson.

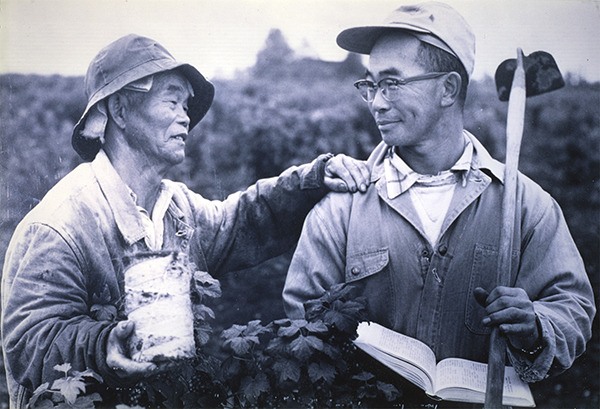

The duo launched the project in 2013 and say they are working to track each of the 121 individuals who were forced to leave Vashon, determine what camps they went to, their experiences while interned and where they went after the camps. They are also trying to locate photographs of each island resident displaced.

“We are discovering new information constantly,” Larson added.

She and Haulman say they are working toward two major public events: a museum exhibit in the spring of 2018 and an expanded exhibit at the Mukai Agricultural Complex, which includes the Mukai house and garden and former fruit-barreling plant.

The seeds for this project were planted in a previous collaboration, when Haulman and Larson archived nearly 150 years of Vashon’s census data — a project that provided a glimpse into the history of Japanese Americans on the island.

“We had a sizeable population (of Japanese Americans) at one time, and we don’t anymore. We thought wouldn’t it be interesting to explore that,” Larson recalled.

Larson and Haulman, both members of the island nonprofit Friends of Mukai, which is fighting for control of the historic Japanese property in order to revitalize it and open it to the community, said they expect their work to become part of the friends’ website and intend to include extensive information there. They hope to be fully ready by the time of the museum show, they said, and incorporate current technology so that visitors can look at a photo on the wall and then instantly connect to more information online.

They have reached far beyond Vashon’s shores in their research, and Larson noted that they have been in touch with the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience in Seattle as well as the grassroots organization Densho, which has an extensive archive of materials that document the Japanese-American experience.

“The information we are gathering is fascinating, and we want to share it with the broader community,” she said.

The information spans more than a century, from 1900 to 2010. This period begins when some of the first Japanese residents lived on Vashon and ends with today’s Japanese-American residents, who have their own family stories to tell about the war and its effects. The years in between include time when the Japanese-American community flourished on the island primarily as farmers, their removal and imprisonment, and the post-war years, when about one-third of the former residents returned to Vashon to try to rebuild their lives.

To advise them as they work, Larson and Haulman say they have created an advisory panel that includes several Japanese Americans, including descendants of Japanese families that lived on Vashon and others who lived in the internment camps when they were young.

In 2014, the project was awarded a $4,500 grant from 4Culture, which supports arts and cultural efforts in King County. In addition to providing the funds they used to hire a professional videographer to assist with oral histories and to improve the website, the money enabled Larson to travel to Washington, D.C. to look for missing census data and visit the National Archives, where she researched the Japanese-American population on Vashon prior to their imprisonment.

Haulman, who taught Pacific Northwest history for 25 years at Green River Community College, said he does not know when the first immigrants from Japan arrived on Vashon, but the 1900 census shows that seven Japanese individuals — all young men between the ages of 14 and 30 — lived on the island and served as servants and farm laborers at that time. By the 1920 census, the population had grown considerably — to 89 individuals, and by 1940, to 123 men, women and children, with most of the men working as farmers and laborers.

In the years preceding World War II, Vashon’s Japanese-American residents were very much part of the Vashon’s fabric, Haulman and Larson said. Students participated in school sports; there were social gatherings at the Mukai gardens, and, in 1932, when a new high school was built, a Japanese-American community group donated 100 cherry trees. But by 1942, the war had intervened, and some 120 islanders were forcibly relocated to the Tule Lake Relocation Center in the California desert.

When Haulman moved to the island in the 1970s, he said he was told that the island’s Japanese-American residents were historically considered friends, that many islanders stayed in touch with them during the war and that many came back after being released from the camps.

“That was the Vashon story, but it was not quite that way,” he added. “There were incredible acts of kindness that transpired here, and there were incidents.”

The federal government kept records on all the people who were interned, and that information is available in the National Archives. There, Larson said, she learned more details about one of those incidents — a fire in which three islanders burned down four homes they believed all belonged to Japanese families. The homes were ruined, along with all the household goods and farm equipment for one family.

Through an advisory board member, Larson and Haulman were able to find the descendants of one of the families whose home was lost in the fire and share information from the National Archives with them. Beyond sharing stories such as this, the pair say they are trying to let families know about the considerable information at the archives, but much of it must be requested by family members themselves. Haulman added he and Larson are asking the families if they would be willing to share information once they receive it — but are proceeding with care.

“We are moving slowly and deliberately and trying to be sensitive to individuals and families,” he said.

Beyond the immediate goals of creating exhibits and online resources, Haulman and Larson say they would like to create a driving tour of the many farms owned by Japanese Americans before the war, some of which are still working farms, others of which are grown over, and they would like to have a marker on Vashon, possibly at the Mukai property or the Village Green, recognizing the Japanese-American residents of the island, their removal and confinement.

While illuminating a piece of Vashon history, all the measures would serve a larger goal Haulman and Larson say they share: making sure what transpired in the 1940s never happens in this country again.

“The best way to do that is to make sure that people know what occurred and the consequences of what occurred,” Larson said.

It is the same motivation that has led Gruenewald to share her story over the years, including some of details of the painful day she and her parents said goodbye to her brother at the camp in Wyoming.

“The only reason why I agreed to participate in this sort of thing is so that it will not happen again,” she said. “I feel very strongly about that.”

For more information, see vashonhistory.com.