Have we moved on from the femme fatale?

I’m interested in the question because on April 29, in tandem with Beachcomber Editor Elizabeth Shepherd, I’ll be speaking at the Vashon Center for the Arts about the classic femme fatale of Hollywood film noir.

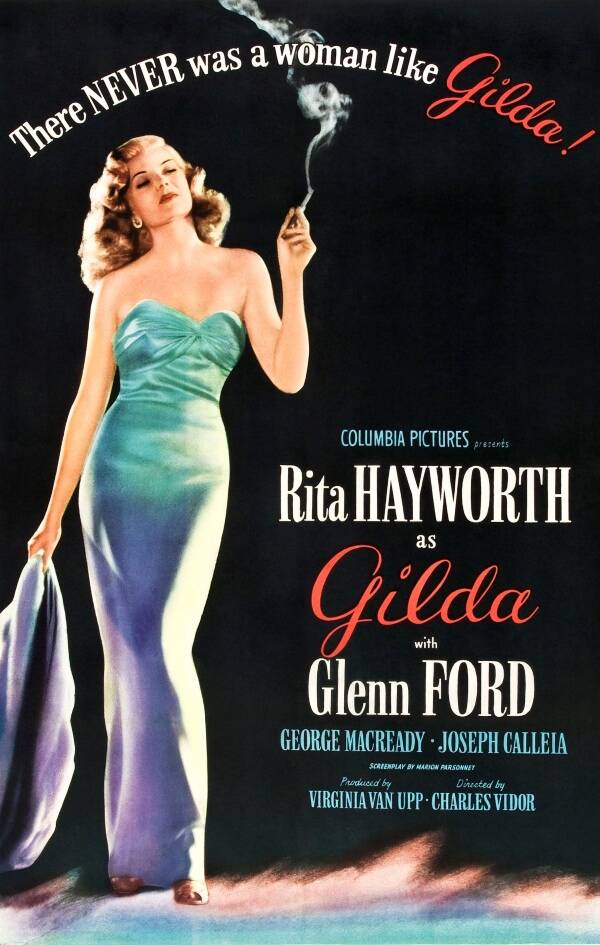

Perhaps you know the type: an alluring vixen who, through the skillful deployment of her feminine wiles (and the occasional spellbinding ankle bracelet), lures men to their doom. Think Barbara Stanwyck in “Double Indemnity,” or Rita Hayworth in “Gilda.”

In our talk, I’ll argue that these femme fatales have gotten a bad rap over the years. From Eve to Cleopatra, from Mata Hari to Monica Lewinsky, world culture has had this tendency to blame the supposed spider women.

But maybe we’re evolving a little. Consider the case of Stephanie Clifford, better known to the world as Stormy Daniels, whose alleged sexual collisions with Donald Trump resulted in a hush-money payment.

Daniels, a porn star with a keen eye for publicity, would seem to have the attributes of a femme fatale. But Trump fans didn’t believe the story or didn’t care, supporting Trump’s contention that he could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot someone without losing supporters. (And if he had sex with a porn star in the middle of 5th Avenue? Same, I guess, but ewww.) Trump non-fans saw the behavior as typical on the ex-president’s part. Either way, hardly the scenario of the classic femme fatale leading a helpless man astray.

If our culture is retiring the femme fatale type, it may be because men are less in charge of framing the conversation. The overwhelming majority of movies from the prime noir era (approximately 1944-58) were made by men; only one woman, actress Ida Lupino, managed to direct in the style. Film noir emerged as World War II was ending, and the genre took some of its edginess from the shifting realities of American life: women had entered the workforce and discovered new freedoms, traumatized men were returning home, and both men and women had to wonder what went on during those years of separation.

You can see noir women as projections of male anxiety. But an interesting thing happens when you watch the movies: these women may be on the wrong side of the law, but they’re awfully fun to watch.

When bored housewife Stanwyck steers insurance agent Fred MacMurray into killing her rich, unpleasant husband in “Double Indemnity” (1944), or streetwalker Joan Bennett fleeces fuddy-duddy Edward G. Robinson in “Scarlet Street” (1945), you are watching naughty behavior, of course. But you are also seeing determination and intelligence and wit, embodied by powerhouse actresses.

When Jane Greer bamboozles Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas in “Out of the Past” (1947), the men are so easily duped you might find yourself taking inordinate pleasure in this scarlet woman’s machinations.

I argue that the men in these noir films, far from being innocent suckers, are just as liable for their own downfall. If not already walking the shady side of the street, they nevertheless know what they’re getting into, and usually earn their comeuppance. And yet we call the women fatal.

As Orson Welles’ character tells us in the opening narration of “The Lady from Shanghai” (1947), “When I start out to make a fool of myself, there’s very little can stop me.” Give that character credit for having self-awareness about being a moth willingly diving headfirst into the flame. In this case, the flame is Rita Hayworth, as a woman with a questionable past; she’s now married to a wealthy lawyer but still capable of flirting with Welles’ character, who works as a deckhand on hubby’s yacht.

The Hayworth-Welles connection gives “Lady” an extra layer of intrigue because the two were in an on-again, off-again marriage when the movie was shot — and Welles, as writer-director as well as co-star, doesn’t flatter himself with his portrait of a chump. As in so much film noir, neither man nor woman emerges very admirably.

I suppose that’s the point I’ll try to make on April 29. One reason film noir plays well with modern audiences is that the characters are flawed, edgy, and capable of making enormous mistakes. Forget about the femme fatale. There’s plenty of blame to go around.

Robert Horton, islander, writer, teacher and curator, was the longtime film critic of the Seattle Weekly and the Daily Herald (Everett, Washington) and a regular contributor to Film Comment and other magazines.

His talk and discussion, “In Defense of the Femme Fatale,” will be presented at 7 p.m. Saturday, April 29, at Vashon Center for the Arts. Get tickets at vashoncenterforthearts.org.