James Broughton’s words seem to adorn Stephen Silha’s life.

They hang around his neck, carved into a delicate silver pendant made by his partner, Gordon Barnett: “This is it and I am it and you are it …”

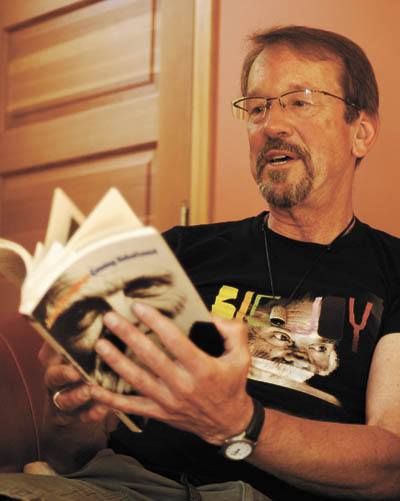

They’re emblazoned across his chest, on a black T-shirt that says, “Big Joy.”

And they grace a sign that Silha carried in the Seattle gay pride parade a month ago: “Follow your own weird.”

Now, Silha, a Vashon writer, educator and civic activist, wants to bring these words and the man who embodied them to life.

Silha is making a documentary about Broughton — a man famous in some circles, little-known in others, but influential by almost any measure. His avant-garde films spawned the West Coast experimental film movement, and his poetry and writing — all told, he published 23 books — helped give rise to the beat poetry of the early 1960s.

But it’s not simply his artistic influence and literary genius that Silha wants to celebrate in the documentary he’s begun to craft. It’s also Broughton’s world view and life philosophy — a profound belief that life is to be lived fully, that finding joy in one’s work can be our greatest contribution.

Another one of Broughton’s phrases captures this belief, Silha noted, a phrase inscribed on his tombstone in Port Townsend, where he lived the latter part of his life until his death a decade ago: “Adventure, not predicament.”

Silha’s documentary, he hopes, will not only celebrate this man’s remarkable life but also provide “a humorous antidote to the cynicism and materialism of our age,” he said.

“If everyone’s following their own weird, the world will be a better place,” Silha added during a recent interview in his small writing cottage.

“The world will be more joyful. Bureaucrats will be less bureaucratic. Educators will be more sensitive. … Churches will be less prescriptive.”

On the wall of his writing cottage, a poster-sized piece of paper captures his documentary’s intention: “to create more joy in the world by inspiring people to follow their own weird.”

Silha is the executive producer of the documentary, a film he hopes to complete by 2013, the centennial of Broughton’s birth. Eric Slade, whose documentary “Hope Along the Wind” profiled gay rights activist Harry Hay, is the director; the cinematographer is Ian Hinkle, who recently directed “The Long Road North.”

Silha is calling his project “Big Joy,” a name Broughton was given by his publisher many years ago.

Broughton’s life — documented in his autobiography, “Coming Unbuttoned,” and described on Silha’s Web site, www.bigjoy.org — was rocky, rich and unorthodox. His father died during the 1918 flu epidemic, when Broughton was 5; four years later, his overbearing mother, as Broughton described her, sent him to military school to try to break him of his feminine ways — an effort that backfired when Broughton, at age 16, was kicked out for having an affair with another student.

He began working with film in the 1940s, producing several avant-garde films both here and in Europe. His most famous, a 19-minute short called “The Bed,” released during San Francisco’s 1967 Summer of Love, won several awards and garnered considerable attention; described as a “merry allegory” by one critic, it broke many taboos at the time for its unabashed full-frontal nudity.

All along he wrote poetry — some of it simple and whimsical, some spiritual and philosophical. A player in the Beat Poetry movement, he was dubbed the “unofficial poet laureate of San Francisco” by poet Alan Watts.

He also had rich and numerous relationships, Silha said; among his paramours were the famous film critic Pauline Kael, with whom he had a child, gay activist Harry Hay, and Suzanna Hart, whom he married.

Silha first encountered Broughton and his work in 1979, when he saw two of his films at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and was deeply moved by their message and artistry.

Ten years later, Silha said, he met Broughton at a men’s gathering in Breitenbush Hot Springs in Oregon, where he and Broughton were coincidentally assigned to the same cabin. A couple of months later, a mutual friend invited Silha to a dinner party in Port Townsend, where Broughton had moved with his partner, Joel Singer.

Thus began what turned out to be a decade-long friendship and mentoring relationship — Broughton helping Silha with his poetry, Silha working with Broughton on his prose, a kind of writing Broughton found difficult. Silha traveled to Port Townsend at least once a month during that final decade of Broughton’s life, and Broughton, who loved ritual, would come to Vashon to celebrate Silha’s birthday or for Thanksgiving.

Broughton was deeply inspirational to Silha, he said, showing that one can fall in love at any age (he and Joel Singer got together when Broughton was 62), living a life that defied simple boundaries and modeling how one can grow old gracefully.

Silha was one of a handful of friends at Broughton’s side when he died. His final words, he said, were, “More bubbly, please.”

Today, Broughton’s influence seems to permeate Silha’s home and life. On a long wooden table in Silha’s living room that he calls “the shrine,” a black-and-white photo of Broughton stands next to a ceramic urn that holds his ashes. Other photos of Broughton adorn both his living room and his writing cottage.

Broughton’s poetry also seems a part of Silha. As Silha glanced at his garden, he suddenly began to recite one of Broughton’s most famous poems, “The Gardener of Eden”: “I am the old dreamer who never sleeps,” he began. “I am timekeeper of the timeless dance.”

A few moments later, when discussing Broughton’s death, he recited another poem: “This is it, this is really it, this all there is, and it’s perfect as it is.”

Silha said his work on the documentary is both exciting and challenging — and at times, a race against the clock. Last week, he interviewed Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the publisher and writer, now 90 years old, and a longtime friend of Broughton’s. Kael died a few years ago, before Silha had launched the project; Hart, his former wife, has Alzheimer’s.

Fundraising is also a challenge. Silha needs $304,000 to make the film; so far, he’s raised about $17,000. He plans to hold fundraising parties and performances all along the West Coast, from San Francisco to Vashon — events that he hopes won’t simply raise money for his ambitious project but also add momentum to the Big Joy movement.

“Hopefully, people will go out of these events following their own weird,” he said.

But like Broughton, Silha is an exuberant and confident man — and on his good days, he said, he feels certain that he and his team will be able to bring the project to completion. He also feels confident that it will fully pay tribute to a man he loved.

“I want the documentary to be as pathbreaking as a documentary as James’ films were to film,” he said.

“James and his life are the lens through which we’re looking at this Big Joy concept,” he added. “Yes, it’ll be about him but also what this Big Joy theory is all about.”

For more information about Stephen Silha’s project, visit www.bigjoy.org.