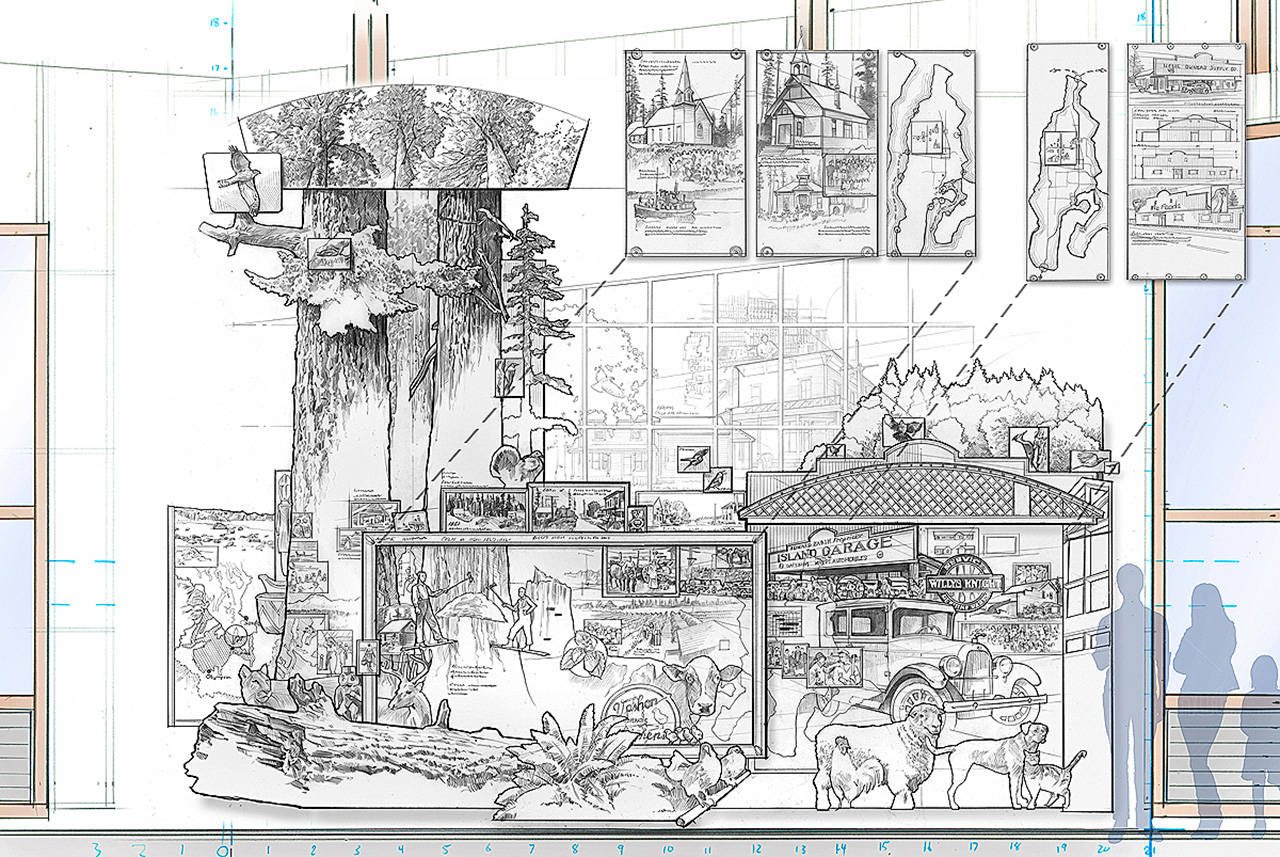

Change is all around us all the time, though rarely do we stop to consider its trajectory from a single central point. Yet, for the last eight months, that’s exactly what island artist, illustrator and — full disclosure — my husband, Bruce Morser, has been doing in his studio. The focus of his attention has been to illuminate the ever-changing history of Island Center — which now includes Vashon Center for the Arts (VCA) — in a large-scale installation that will be unveiled in its permanent location in VCA’s lobby March 25.

The project arose during the permitting process for the new arts building when King County requested VCA honor the original structures and history of the intersection. Morser, who spent six years as a board member on the VCA building committee, was asked to design a plan to fulfill the county’s requirements. He agreed, and island art patrons Tracey and Janet Bishop stepped up to fund the project.

Yet, the initial suggestion of creating a simple kiosk filled with historical photographs and drawings soon took on a larger dimension — both physically and metaphorically — as Morser delved ever deeper into the history of Center and the island.

“I spent a bunch of time thinking about it, trying to catch a feeling of what the piece might do,” Morser said. “I spoke with old islanders I knew, who introduced me to others I didn’t know. As the connections grew, so did the project. I realized that paying homage to the old pet store at the southeast corner of the intersection was too small a way of looking at it. Understanding how people used Center over the years was equally important. The more I looked into it, the more I realized the area has been used by all types of people for thousands of years, and that helped widen the spectrum of what the project could be.”

Widen it he did, taking the story line back 16,300 years. That’s when Vashon first emerged from beneath the ice sheet of the last Pleistocene and was surrounded by Lake Russell, a body of fresh water that extended south past Olympia.

“Vashon and the surrounding land had not fully sprung back from the weight of the glacier that had depressed it,” Morser said. “So, literally, Vashon was rising up through a changing body of water. The ice had scrubbed any life from the island, so this seemed like a fair place to start the story of living things on Vashon.”

Those living things included three waves of human population — the nomadic hunters, who disappeared 10,000 years ago; the Salish people, who appeared sometime between 3,000 to 6,000 years ago; and the white Europeans, who first arrived in the 1840s.

Using over three dozen pencils, Morser drew on planks of fir and cedar that he cut and glued to specific shapes and sizes. Other images he had printed on sheets of Plexiglas. His goal was to visually capture the transition from an old-growth forest with a mature, indigenous population to the European impact from clear-cutting, establishing townships and the buildings replaced by the new arts center.

“I’ve always been interested in the area between art and illustration,” Morser explained. “Is something a diagram or a piece of art? I’ve tried hard to make this project tread that fine line. I hope it works as a piece of art, but I’ve also tried to load it with information that you can learn from.”

Not wanting to show the past through just old images of European settlers, Morser created a timeline using birds that changed as their habitats were developed.

“There are different birds that live in old growth, in logging, agricultural and residential areas,” he said. “The transit of time can also be told by the wild and domestic animals, from the deer and cougars to early farm and commerce animals like sheep, cows and especially chickens, and house pets like dogs and cats.”

To physically show the evolution of Center and its many layers of change, Morser designed the wood panels to slide across the 15-by-21 foot installation. Believing that history becomes more interesting “if you have to dig through things,” Morser’s panels are interactive and require the viewer to move them aside to see the imagery hidden beneath.

With a series of hand-drawn maps, Morser illustrates the dramatic transition of the island’s independent waterfront communities, each with their own ferry dock, general store, school district and post office, to a unified island with one central town, two ferry docks and one school district. A major instigator of change was the introduction of the automobile around 1915 to 1920. That’s when residents began to focus on belonging to the island.

“I was surprised to learn that being an ‘islander’ wasn’t as significant a concept as it is today,” Morser said. “Being on the water was important because the waterways were the roadways. Water meant transportation, as it did throughout the Northwest then. The original Puget Sound Salish on Vashon knew that — their tribal name means ‘Swiftwater People.’ Once cars were introduced, linking all the small shore-side communities, the sense of an island identity grew.”

Bringing the subject back to Center, Morser explained that the building most islanders refer to as McFeeds began as Ed Zarth’s Island Garage and car dealership.

“To fulfill the original obligation of the project, which almost got lost along with my life, I show a lot of imagery about the building,” Morser said, adding with a laugh that Zarth sold the Whippet, “a quirky automobile — very Vashon.”

Morser heard the story of Zarth’s death from an explosion inside the building first-hand from islander Bob Therkelsen, who was born and raised across the street in the old Fuller Store. Therkelsen watched the corner change over the years as first the Baptist Church came down to make way for Zarth’s Garage — that later housed McFeeds and other short-lived businesses — which VCA then replaced.

“Looking at the evolution of this small, rural intersection was an ideal lens through which to see how Vashon grew to what it is today, and then as a portal to try to feel how the entire Northwest came of age,” Morser said. “That’s why my interest in this project grew commensurately the more I learned. One of the unexpected outcomes is that for the last 30 years, I’ve loved living here, but I love it much more now.”

Morser gave a final shout-out to all the people who assisted with the project including Bruce Haulman, who “was incredibly helpful in digging up history and sorting my facts, and who I look forward to presenting with after the reception.” Other instrumental people include Reed Fitzpatrick, whose knowledge is “encyclopedic and who is burning with interest in the island;” Tom DeVries, who elucidated the island’s natural history; Rayna Holtz and her understanding of the indigenous population; Bianca Perla, who helped with animal references; and the “interviews with islanders too many to reference.”

Unveiling ceremony

Morser’s piece, “Honoring Center: At the Intersection of Art and History,” will be unveiled in the lobby of the Kay White Hall during a ceremony from 2 to 4 p.m. Saturday, March 25.

Following the unveiling, Morser and island historian Bruce Haulman will talk about the interweaving of Center’s past with the challenges of capturing that history in a piece of art.