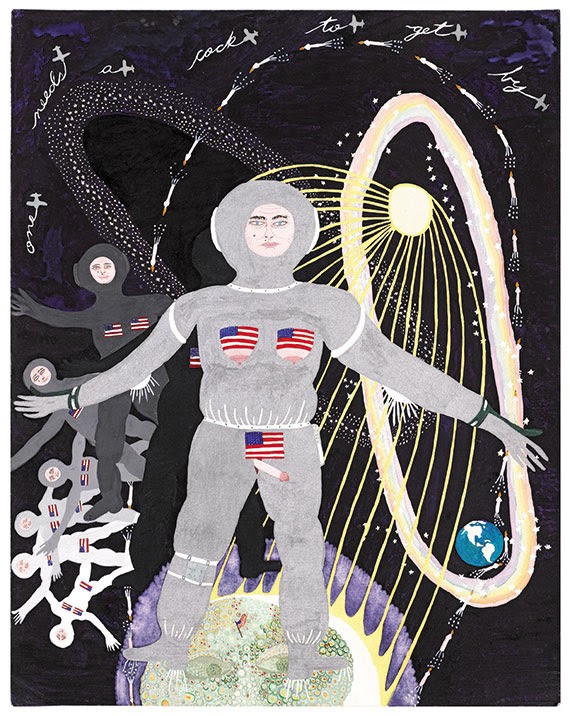

It’s taken over 40 years, but the art world has finally caught up to island artist Ann Leda Shapiro. Two of Shapiro’s paintings, once deemed offensive by New York City’s Whitney Museum of Modern Art, this year became part of the Seattle Art Museum’s permanent collection. The censored painting, “Two Sides of Self,” and another from the same era, “Woman Landing on Man on the Moon,” now take their seat in SAM’s small but growing holdings of 20th century art by women.

In her sunny studio overlooking Tramp Harbor — a far cry from the concrete canyons of her hometown New York City — Shapiro recently recounted her artistic journey and the effects of early success and subsequent censorship.

While still in her 20s, Shapiro received a significant artistic nod with a solo show at the Whitney in 1973. It was the nascent days of feminism, and Shapiro’s work explored questions about what it meant to be female or male. But the topic of gender back then belonged in the realm of the avant garde, so much so that the museum censored two paintings out of Shapiro’s exhibit. That stunning experience sent Shapiro traveling an unexpected artistic path, a path that came full circle when SAM acquired her paintings.

“I was shocked (by the censorship),” Shapiro said. “My response was to withdraw from the art world rather than fight it, but I did not internally censor myself. I went back into the studio, and not looking over my shoulder at the art world, I was able to create a truly original body of work that’s getting recognition now. What I thought then was the worst experience ended up the best. What I thought was a tragedy turned into a benefit.”

The benefit Shapiro discovered was the freedom to make art without the strings of social mores attached, and she’s been working steadily — for more than 45 years — ever since.

Shapiro’s artistic life first took shape when as a child she and her mother visited New York art museums, followed by her own daily trips to the American Museum of Natural History.

“I would meander through the museum,” Shapiro said. “That’s how I learned to draw and to fall in love with other cultures. And that’s where I got introduced to Chinese medicine.”

As a university art teacher who taught life drawing for 14 years, Shapiro understood the body well, saying she always worked with “the body as landscape.” But Chinese medicine, which works with the flow of energy called qi, peaked Shaprio’s curiosity about what might lie beneath the skin, below the bones and muscles. That curiosity brought Shapiro to Seattle in 1991 to attend acupuncture school. She’d read the philosophy behind the traditional Chinese medicine, but wanted to investigate, research and understand the system of energy meridians. Never intending to become a practitioner, Shapiro nonetheless fell in love with acupuncture.

She also fell in love with the Northwest and in 1992, moved to Vashon, where she opened her acupuncture practice.

“I only did acupuncture for work then, but I always did my art. Now I have acupuncture days and art days.”

Until recently, Shapiro also only showed her artwork at Puget Sound Cooperative Credit Union, having essentially dropped out of the art scene. Invisible to the region’s curators and art buyers, Shapiro’s art found its way to SAM by a novel and somewhat radical route.

According to Shapiro, her work was acquired by the museum via the conceptual artwork of Seattle artist Michael Offenbacher. With $25,000 of prize money from winning Cornish College’s Neddy Award, Offenbacher and his wife Jennifer decided to work with SAM curator Catharina Manchada to acquire art by women and queer artists for the museum, a decision that didn’t come out of the blue.

In 2012, the traveling show “Elle,” organized by Paris’ Centre Pomidou and featuring women artists from the 20th century, opened at SAM. The museum planned to also exhibit its paintings by women artists from the last century, only SAM had a paltry collection.

“So Matt and Jennifer realized there was a gap and decided they would become collectors and use the money to buy feminist and queer art,” Shapiro explained.

Manchada saw Shapiro’s art as a member of a grant review committee. Next thing Shapiro knew, she got a call from Manchada, then a studio visit and now a spot in SAM’s permanent collection. Manchada had shown photos of Shapiro’s work to Offenbacher, who bought the paintings and then donated them to SAM.

Back in her studio, Shapiro is in the midst of completing several projects — a group of large scale paper cut-outs, a visual memoir of the American Museum of Natural History executed as a series of paintings that she’s turned into a deck of cards plus another children’s book. And after 23 years of working on it, Shapiro plans to finally publish a graphic novel that illustrates the history of Chinese medicine.

“So I’m very patient,” Shapiro added with a laugh. “And it’s been great to live on Vashon, to live out my potential. I’ve even fallen back in love with the two paintings all over again.”