Dockton once had the largest dry dock north of San Francisco, a booming shipbuilding industry and a thriving maritime economy. But to the casual eye, there’s not a trace of the town’s past.

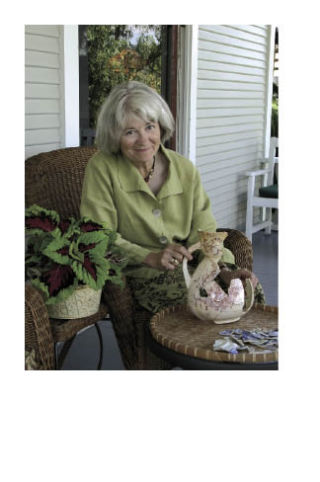

“There are no signs at all that indicate the heritage of Dockton,” said Anita Halstead, a founding member of the Dockton Historical Committee. “There’s not even a ‘welcome to Dockton’ sign — there’s only a Dockton Park sign.”

With this in mind, Halstead joined forces with 17 other residents of the waterfront community and set out to create an interpretive trail documenting the history of Dockton. The group planned 10 signs, on a loop of less than a mile, each touching on a significant aspect of Dockton’s heritage.

Now, the residents are closer to creating that trail, thanks to news this month that 4Culture, King County’s cultural services agency, approved a $5,000 grant to design the signs.

Scott Snyder, the resource director for the King County Natural Resources and Parks department, said the project has been “green-lighted” for funding for construction and installation of the signs, as well as construction of an informative kiosk at Dockton Park, through the county’s Community Partnership and Grant (CPG) program.

“It looks like pretty much a done deal that Anita’s group will get this money from the CPG,” he said. “They just have to go through steps to fill out the paperwork … It looks like there is money for construction of the signs and a kiosk.”

Halstead said Islander Sandra Noel, who has designed interpretive signs for national parks, will design the signs; Islander Cathy Fulton will write the content.

Halstead said that in the coming months, she and others will be interviewing the people who have lived in Dockton the longest and quote a different person on each sign.

Halstead, who calls herself “100 percent Croatian,” said from the 1880s to 1930 the immigrants who came to Dockton were Croatian and Norwegian. But she had no idea of the cultural heritage of her community or of her home — a 1908 craftsman built by Croatians — when she purchased the house in 2000.

“I didn’t even know about this history until I moved in, and began doing a lot of research,” she said.

What she found astounded her — connections to her native country, in her own home and all around her, that she’d never have known about if it weren’t for her own avid interest in history.

“Here I am, living in the midst of this Croatian history and just overwhelmed with the richness of it all,” she said.

She renovated her house, which didn’t have front steps and was assessed a “teardown” by King County because of its age. Today, it is wood-shingled, is freshly painted and boasts an impressive garden that Halstead and her husband Kelly Robinson landscaped themselves over the last eight years. Their garden won second place in The Seattle Times’ Pacific Northwest Garden Contest.

Intrigued by what she was learning, Halstead began to reach out to others in the community and found that they, too, agreed that the history of Dockton should be documented, lest it fade with future generations.

When the group began work in October 2007, she warned the other members that it could be a five-year project — but now it looks like it will be done in two, she said.

“All of a sudden, all these things came to us at once” — the 4Culture grant and the enthusiastic support of those at King County parks, she said. “To have this come to fruition so quickly is really exciting but also overwhelming.”

The walking trail will take a circuitous path through Dockton: It will begin in Dockton Park, continue on Dock Street, take a left onto Stuckey Avenue, turn left onto S.W. 260th Street, turn left onto 99th Avenue S.W. and take a right on S.W. Windmill Street to reach its conclusion.

The first sign will be a kiosk in Dockton Park, explaining the focus and purpose of the trail and displaying a map of Dockton showing the locations of each of the interpretive signs.

The second will describe Dockton’s “dry dock years and shipyard years,” Halstead said. The third sign will be about Dockton’s industry of brick-making.

The fourth will be on the mosquito fleet, Puget Sound’s fleet of thousands of small steamships that reigned supreme from the 1850s to the 1930s. Dockton had its own landing for these boats.

The fifth sign, at the intersection of Dock Street and Stuckey Avenue, will chronicle the codfish dock — now renovated, cedar-shingled and dubbed “the Crab Shack.” It was once a fish processing and canning plant.

The sixth sign will detail the net shed, one of the last remaining in the Puget Sound, where the fishermen still “come and untangle their nets and rework them so they can take them out again,” Halstead said.

The seventh sign will describe the agricultural industry that replaced Dockton’s maritime economy when the dry dock was removed in 1930. On it will be photographs of “acres and acres of all kinds of berries and fruit trees,” Halstead said.

The eighth sign will be a remembrance of the Dockton School, which used to be a hotel. The building has collapsed, but there are photographs of it.

The ninth sign will be placed at the Dockton Store, which is on the National Historic Registry.

The tenth and final sign will be installed at the Dockton Water Association building, what Halstead described as a “fairly old building with a new roof,” and which used to be a school and a community center where social gatherings and dances were held.

The Dockton Historical Committee will give a slide show of the history of Dockton on Aug. 23 at the Dockton Water Association building, at 9710 S.W. Windmill St.