Larry Flynn lives on a back road, but he’s a strong presence on Vashon. His small green house, surrounded by native woods and cultivated gardens, overlooks Puget Sound. There’s a walking trail down the steep bank to a beach below, where an osprey lands as we talk. Flynn explains that he inherited the house from his friend John Thompson, who died almost 20 years ago of AIDS.

“Best friends have such an impact on a person’s life,” he says. Flynn’s life and causes reflect his commitment to honoring his friend.

Vashon commuters know Flynn as an early-morning Metro bus driver. Music lovers may recall the annual Vashon concert by the Total Experience Gospel Choir, a fundraiser Flynn organizes for Bailey-Boushay House, a Seattle residential care center and hospice that serves mainly people with AIDS. Vashon Thriftway shoppers may not know Flynn, but they’ve likely met the volunteers he mobilizes for “Care to Shop,” a donation drive for the Lifelong AIDS Alliance.

Flynn’s contributions to the community are focused on support for people living with AIDS and on prevention. He’s been living with HIV since 1985. After his best friend’s death of AIDS in 1989, Flynn says, “It took me about two years to get over the personal issues, the denial and the anger. After that, I decided I would get proactive about raising some consciousness.”

Flynn talks freely about his life, with good humor and tough-minded honesty. He’s a big man with a strong face, who looks like he spends a lot of time outdoors. He wears a wide-brimmed hat, explaining that the medications he takes make him sensitive to sunlight. What the medical establishment calls “manageable pill therapy” is not so easy to live with. He points out that the pills that have saved his life also wreck his appetite and cause neuropathy that makes his feet painfully sensitive to cold and even to standing up.

“The medicines are amazing; I’m grateful to be here. But people need to be aware that he side effects are serious.”

Flynn is concerned that public AIDS education minimizes the risks of acquiring HIV and underplays the difficulty of managing the illness. To emphasize the challenge of living with AIDS, he once sang “The Circle Game” at a church gathering (he and Thompson shared a love for Joni Mitchell songs). Before he sang, he handed out lyric sheets to the congregation. One in five of the sheets had a red underline, and he asked members who had received them to raise their hands. “The red lines were the one out of five people who can take these drugs, and maybe negotiate the illness. For everyone else, good luck — you’re on your own.”

Flynn’s consciousness-raising tactics are direct — he’ll do whatever he can to prevent risky behavior. At the Total Experience concerts, he gives a little talk aimed at young people. He acknowledges, “I sound like someone’s grandfather, but it’s just the truth.” His mini-lecture is focused on AIDS prevention. “I tell them, ‘Preserve your virginity, children… if you challenge the line, use condoms and rubber dams.’” Flynn laughs, reflecting on his own youth. “I never thought I’d be talking about the virtues of the good life. I thought you should get it while you can, walk on the wild side! But there are so many pitfalls in promiscuity.”

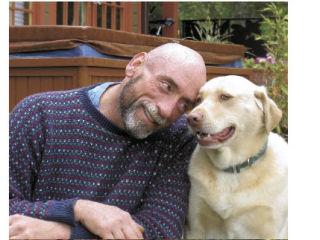

Born in Seattle and raised in California, Flynn returned to Washington state as a young man. His friendship with John Thompson brought him to Vashon; the two were living as housemates on Beall Road when Flynn got the Vashon driving route. Today, Flynn’s home shows his love for nature and living things. A sweet-tempered dog named Gordon kisses a visitor’s neck, and cats wander under the trees. He recently completed refinishing an outbuilding as a guest house, which he calls “the Last Resort.” It’s a cozy, natural setting, with a hot tub, under the big-leaf maples and surrounded by spring flowers.

Flynn’s projects reach many people. On the third Saturday of the month, the Lifelong AIDS Alliance sends a van to the Island to collect the contributions of Vashon shoppers. Some of it goes to Vashon residents, who can choose what they need directly from the van, and the rest serves people in Seattle. The program is vital for people with a limited income who need extra nutritional support. Flynn underlines that it’s not all about health food. “Peanut butter is good. Getting enough fat is an issue. Cookies and munchies are great — the body goes through some amazing changes with this illness, and requires higher protein and higher fats.”

Flynn’s stories show how he’s learned from experiences the costs of certain indulgences. He’s not moralistic, but encourages people to assess the risks of a wild life. “The flesh does things it wants to do all by itself … even though my heart and mind and soul know what the correct thing to do is.” He laughs at himself, but he’s totally serious. “ Drinkin’ and smokin’ and trampin’ around — things that are measurably detrimental for you — this flesh wants to do all of that. “

He doesn’t talk directly about his faith until he’s asked. “I’m a Christian because I’m so broken up I don’t know how to function with out that as the center … If you want a room lit, you turn the light on all the way. Christ is the light — the further I walk away, the harder it is to read.”

Faith is the bedrock, underneath Flynn’s humor, earthy language and passionate advocacy. It’s not something he pushes on others. “I don’t have an issue with who worships what,” he says. He’s still honoring his best friend, still trying to help others, living his beliefs every day.