Last month, a now infamous New Yorker article created a veritable tsunami of panic and hand-wringing with its vivid description of the destruction a full rupture of the Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ) would unleash upon the geographically unlucky residents of the Pacific Northwest — particularly those living west of I-5.

To some, more surprising than anything in the piece or the follow-up that appeared a week later, however, was the panicked public reaction to information that scientists and emergency management personnel on the West Coast have known — and been talking about — for many years.

“Cascadia is not a new worry,” Rick Wallace, president of VashonBePrepared’s executive committee and its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) team lead said. “Emergency managers in the Pacific Northwest have been preparing for and putting out messaging about this for a long time.”

That preparation includes a major, multi-jurisdiction exercise called Cascadia Rising, that is scheduled to take place next June. And Wallace is on the planning committee.

Similar to past emergency operations and management drills such as Sound Shake 2010 and Evergreen Quake 2012, the Cascadia Rising event will work from a pre-determined scenario, this one being a magnitude 9.0 earthquake along the length of the CSZ fault and its subsequent tsunami.

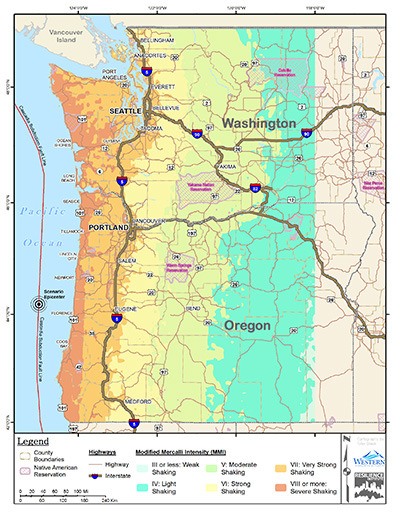

The CSZ fault lies offshore in the Pacific, running parallel to the West Coast for 700 miles, from California to British Columbia. Subduction is the term used to describe one set of tectonic plates sliding beneath another, which is what is happening along the length of the fault. With a history of the plates getting “stuck,” stress along the fault builds until it eventually ruptures, as though being popped open by a giant crowbar.

While 9.0 might seem to be extreme, subduction zones produce the world’s largest earthquakes, with 8.0 being at the low-end of their range of magnitude.

The June event will be a functional exercise, meaning the focus will be on EOC to EOC communication, operation and coordination, and will involve emergency management teams at the city, county and state levels as well as several federal agencies, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Participating in the exercise are Washington, Oregon, Idaho, British Columbia and Washington, D.C.

“There will be some field activity added to the functional exercises for this one,” Wallace noted. “It’s been confirmed that we’ll have JLOTS participating.”

Unlike previous drills and exercises, the U.S. military will be involved in Cascadia Rising, working on its own objectives in parallel with the state and local teams. JLOTS stands for Joint Logistics Over the Shore and involves the loading and unloading of ships without fixed port facilities — in this case, it means getting supplies to and evacuating casualties off of the coast as well as Vashon, because in the scenario, Wallace explained that the island will lose both ferry terminals — one to a dock rupture, the other to a landslide. Other pieces of his Vashon scenario include a lost substation leaving the island without power, one fire station collapse that crushes a fire truck and medic vehicle, a landslide that takes out 45 homes and casualties, including seven deaths and more than 100 injured.

“The idea here is to understand what’s going on, make a plan and take action,” he said. “We have to figure out how to do the most good we can for the largest number of people with what we have on hand.”

Another military group involved in the exercise was recently spotted by a few eagle-eyed islanders, as the SeaBees — members of the U.S. Naval Construction Forces — conducted practice dives in Quartermaster Harbor a couple of weeks ago. Their job will be to construct off-shore docking facilities for aid and supply vessels.

The exercise will last for four days.

But as significant an undertaking as Cascadia Rising will be, Wallace believes that nothing can replace individual preparedness.

“The vast majority of people who survive catastrophes like this either rescue themselves or are rescued by neighbors, not responders,” he explained. “People are lulled into a false sense of security when we talk about how much preparation we’ve done, but it’s important to understand we will not be able to rescue you.”

And while written to be informative, pieces like the New Yorker articles often do more harm than good, Wallace added.

Referring to detailed descriptions of the nightmarish aftermath of this particular earthquake, he became frustrated.

“All of this hasn’t agitated the community enough for people to run out and get ready,” he said. “So scaring the beejesus out of people is clearly not an effective way to work.”

He went on to say that in his experience, people generally have one of two reactions to being confronted with this kind of information — either they panic and go into denial, or they become fatalistic about it. And both reactions are obstacles to doing the things that he thinks everyone should do to be able to best help themselves or their family and neighbors.

Acknowledging that it can be overwhelming to try to prepare for something like a major CSZ event, Wallace had some suggestions.

“Think about it as though you’re preparing for a really bad storm,” he offered. “Those happen regularly enough around here, and the preparation is pretty much exactly the same.”

Specifically, he suggests having a 10-day supply of food and water, emergency lighting and power and a heat source. He also recommended designating an out-of-state family member or close friend as a contact, taking a Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) course and starting a Neighborhood Emergency Response Organization (NERO).

“If it’s overwhelming, just do a little bit at a time,” he said. “Each time you go to the grocery store, pick up one or two things. Before you know it, you’ll be set.”

One tool that seismologists as well as several local politicians believe might go a long way toward preventing many of the predicted casualties is an Earthquake Early Warning system (EEW). Already in use in Japan, two prototype systems are currently being developed in the U.S. — one in California and one in Washington.

“The principle is that we watch for the start of a quake,” John Vidale, director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network said. “Then we can estimate the location and size or power of it, so we have an idea of when the shaking will start.”

He explained that seismic waves move several miles per second, so the proximity and depth of a quake in relation to the warning area will determine how much warning people get, citing a range of a few seconds to a few minutes.

“If a Cascadia rupture started off the coast of California, it could take up to 5 minutes for the whole fault to break,” he noted. “That’s a good amount of time to do what needs to be done to stay safe.”

Vidale said that studies have shown that the majority of injuries and fatalities that occur during earthquakes are caused by people being knocked down or crushed under objects that fall. With even a few seconds of warning, it’s suggested there could be anywhere from a 10 to 50 percent reduction in casualties. Warnings can be delivered via cell phones, sirens and emergency broadcasts on TV and radio.

California is about five years ahead of Washington with its EEW, but the ultimate goal is for the West Coast to be connected, Vidale said.

Sympathetic to this endeavor are Sen. Patty Murray and Rep. Derek Kilmer, who represents Washington’s Sixth District, located in the western portion of the state. Both have lobbied for federal funding for the EEW, as well as prevention and mitigation money from FEMA.

“That New Yorker article was frightening but it doesn’t do any good to wring our hands,” Kilmer said. “We need to make the effort to be prepared.”

Kilmer sits on the House Appropriations Committee and noted that the budget caps imposed by sequestration have significantly hampered his efforts.

“FEMA’s mitigation fund for the entire country right now is $25 million, which is $175 million down from the president’s budget,” he said.

Mitigation funding is used to help communities prepare before disasters strike. For example, Ocosta Elementary School in Grays Harbor county received a grant from FEMA to build the first tsunami vertical safe haven in North America — big enough to hold all 700 students and staff in the entire district.

“More progress needs to be made and more funding is needed,” Kilmer said. “We need to make the investments to keep people safe. We need to do better.”