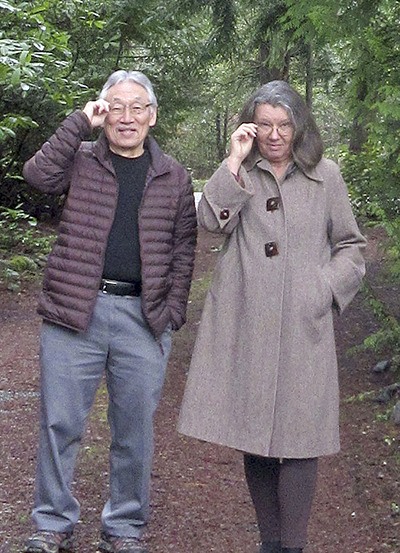

Listening to island writers Ann Spiers and Lonny Kaneko talk about their long-term friendship sounds more like the banter of a comedy team than that of Vashon’s inaugural and current poets laureate.

The two accomplished poets met with The Beachcomber last week to discuss the many points of connection in their lives and the upcoming reading of each poet’s new work — “Weather Station” by Spiers and “Coming Home From Camp and Other Poems” by Kaneko — slated for 6 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 18, at the Vashon Bookshop.

Ask when the two first met, and the answer runs along the line of “1972? No, it was ‘73. Or was it ‘74?” “When did you break your foot, Ann?” Then the pair is off and running with memories they mockingly refer to as “Cultural Notes.”

Spiers begins, saying Lonny grew up in … and Kaneko finishes the statement citing “(Seattle’s) Central District, across from Yessler Terrace.” Spiers was raised on Capital Hill as a “post-war Catholic” with a fascination for all things Japanese, while Kaneko spent several years of his early life at Minidoka, an internment camp for Japanese-Americans during World War II. Despite their disparate origins, the writers share a mutual time line of friendship. They agree on not when but where they met: in an Aikido class in a bowling alley in Seattle, “on the edge of the original Chinatown,” Kaneko said, “where Ann hurt her foot.”

The following nexus occurred at the University of Washington, where Kaneko took classes with poet Theodore Roethke and Spiers later studied under poet Nelson Bentley, though neither intended to become a poet. Spiers had started a master’s degree in play writing, then switched to poetry when her plays where deemed “too feminist.” Kaneko, an English major, took Roethke’s poetry class to fulfill a requirement, having never written a poem.

Then came the Highline School District.

“Lonny was my boss,” Spiers quipped, while Kaneko fired back, “She quit on me, and that’s the funniest point.”

For years, the two teachers commuted together from Vashon. According to Spiers, their traveling conversations “were about how to teach a particular student, a class, or a text or how to teach something better.”

All the while, as they taught, each poet kept writing. Why do they write, and why does poetry matter?

“It’s a way to figure out who I am. If you know who you are, then you have nothing to say. But there’s a lot to figure out and that means you talk about the world you live in,” Kaneko said. “Cal (Kinnear, Kaneko’s co-poet laureate for 2016) was writing about the importance of place recently. It’s different for me — the problem with Vashon is that everything is so good. Elsewhere, there is a lot of concern. So, I write about stuff brewing up from the past.”

Spiers said she “writes to feed my curiosity about landscape or history or family and to make my experience have value.”

She added that in her monthly haiku group, which began 15 years ago, the conversation always ends up that “where we live is a luxury.” It is also a place where people read and talk about poetry, which is a rare community, she said.

Poetry is equally upheld on Vashon by publishers like writer Jeanie Okimoto, who will introduce Kaneko and whose Endicott and Hugh Books printed Kaneko’s “Coming Home From Camp and Other Poems,” which portrays life among Japanese-Americans during and after World War II.

Spiers’ new work is a collection of broadsides, or poems, printed on sheets of paper with a design or illustration. In Spiers’ case, the images are icons from the International Weather Symbols, which link to her poems about climate change.

Poetry also thrives here, Spiers said, because there are venues for poets to do a reading. Kaneko agreed and pointed out that the island “calls a certain person to live here.”