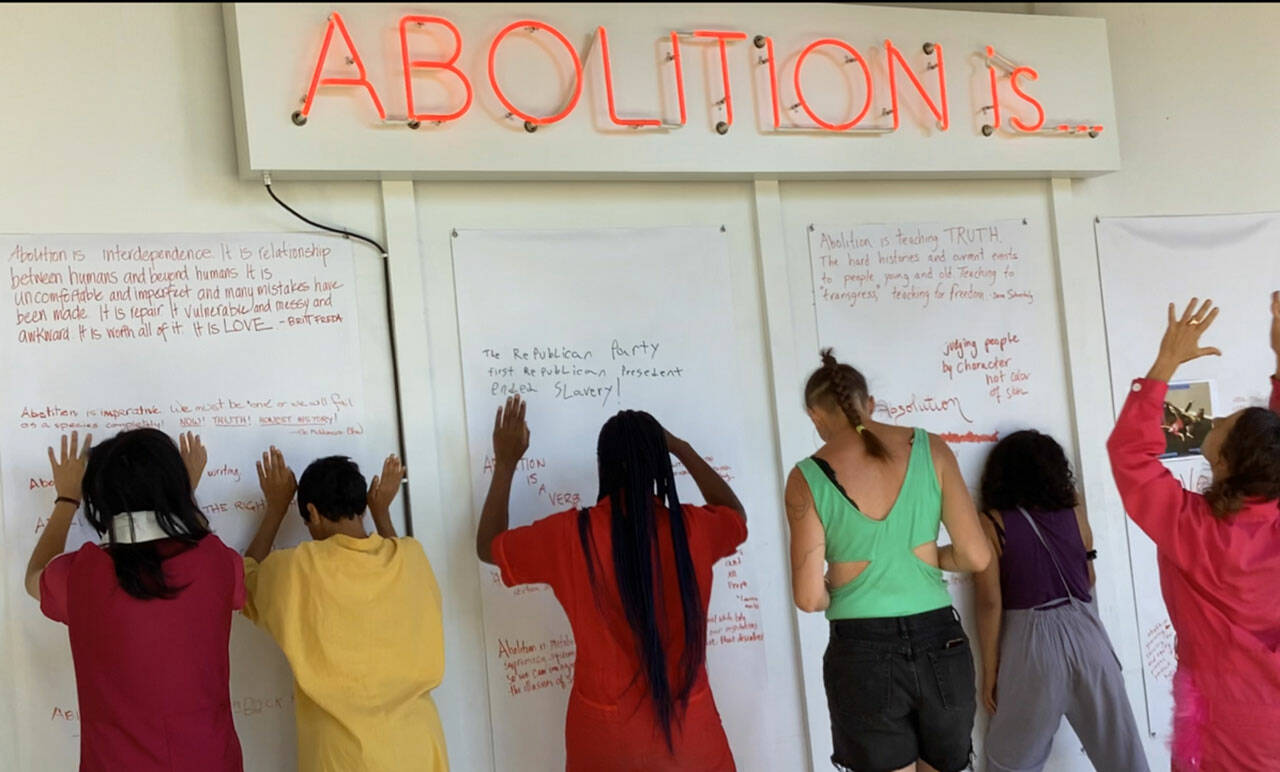

The “ABOLITION IS .. a dance response” project, performed on Aug. 19 in the Vashon Center for the Arts breezeway, called for a majority Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) group of eight dance artists to interact with Patrisse Cullors’ neon artwork installation at Vashon Center for the Arts.

The work used dance improvisation and practices similar to “somatic abolitionism,” a term coined by Resmaa Menakem in his book “My Grandmother’s Hands.”

The dance collaborators (whose work is cited below) included BIPOC guest artists Lesly Rodriguez (California), S Arjunwadkar (Vermont and Pune, India), Helena Zhao (Washington) and Skyla Miles (California), who are multidisciplinary artists at varying stages of emergence, and the international performer mayfield brooks (New York) who brought “Improvising While Black” to Vashon in February 2019.

White-bodied artists included Karen Schaffman (California), Alia Swersky (Seattle), and islander Karen Nelson, who also convened the project.

The work combined reflection and action, confusion and clarity. It was obscured, almost hidden in the breezeway of VCA, but it was also blatant to those within range of receiving its gift through sight, sound and other ways of experiencing.

Some viewers, it appeared, had to run away.

One observer reported that the context of the performance, set within Cullors’ words “ABOLITION is…”, influenced her view.

She mentioned some images that came to her mind, “the vision of long strips of colorful fabric was making a wall, or jail; a dancer climbing painstakingly up a huge chair bringing to mind the journey of the oppressed, only to be knocked down again; a dancer crawling along a ditch disappearing out of view and then rising up at another location brings feelings of being shot down and rising again.”

She said, “One of the dancers engaged my eyes and asked, what do you feel about abolition? I had no words, only contorted emotional expressions conveyed by my face which the dancer turned into words for me — fear, sadness, confusion.”

The viewer added, with candor, “Being a privileged white woman with a low threshold for discomfort, when the chaos became too much for me, I made my excuses and left.”

The performance was an inquiry of the body and of politics. It was a marriage of breathing the joy of being alive and the confusion of relying on the destructive system to survive. It questioned, when did humans stop caring?

“ABOLITION is …a dance response” was a performance that asked itself, what is performance?

The performers knew how to rest while standing and lying down on the ground, and they danced in physical contact, touching each others’ bodies’ after years of pandemic lockdown. The performance attempted to nurture everyone — the performers, the audience, the ancestors called to witness — to care for each other through gentle movement, meditation, and presence. The dancers knew how to be together and apart, to be lonely, and powerfully united.

A second observer said they were struck by how “the piece didn’t have a typical start. The performers were calmly waiting for the beginning to happen, which also calmed and attuned me to the performance — then I noticed the dance was underway.”

“Abolition is…. a dance response” was the nature of ritual healing and ritual envisioning. It empowered voices and visions of the past while dancers were shaking on shaky ground and crawling through a dry creek bed. One dancer was resting on pebbles while stones were placed around the edges of her body. She got up, leaving her body outline form on the concrete.

A shiver of recognition ignites responses from the performers: “ABOLITION is… no police, no prisons. It is stop owning! It is white abolitionists getting in the way. It is radical resistance to plantation economy. It is Harriet Tubman. It is organizing to get people out of prisons. Abolition is questioning settler mentality domination. It is about asking, how am I in relation?”

Gratitude goes out to white-bodied activists’ financial and in-kind contributions that supported this work. The project also received an emergency grant from Foundation for Contemporary Arts that paid BIPOC artists honorariums, thereby acknowledging the intense emotional and physical labor that accompanies their cultural work. White-bodied collaborators chose to forego honorariums as part of their activism.

See photos of the performance at vashoncenterforthearts.org/abolition-is, and watch performance footage at tinyurl.com/mt5rebbb.

Karen Nelson lives on Vashon Island and is a touring dance maker who convened and participated in the project.