An osprey flew overhead shortly after Abel Eckhardt and his volunteer-partner for the evening, teenager Peter Evans, eased their red canoe into Meadowlake Pond in Island Center Forest on a recent Wednesday night. The light was beginning to fade, and the pond, nearly inaccessible due to the thick walls of brush that surround it, was still.

Then an unearthly sound broke the silence — a loud, low foghorn-like call, the “come hither” of a male bullfrog. Seconds later, another baritone announced his presence. Seconds later, another.

As a flash of lightning lit up the sky and another bullfrog called for a mate, this small lake seemed like a Louisiana bayou, not a willow-fringed pond in Western Washington.

But of course, Eckhardt and Evans weren’t in the deep south, and these bullfrogs, happily native in other parts of the country, don’t belong here. Huge by native-frog standards, they’re known to nab native newts, salamanders and occasionally birds. They sometimes take over ecological niches, displacing the native red-legged frog and other amphibians. With few predators in these parts, bullfrogs reproduce quickly and, in some places, by the thousands.

As a result, Eckhardt, land steward for the Vashon-Maury Island Land Trust, and a crew of volunteers have engaged in a decidedly grim task over the last three years. Each summer, for those few weeks when the bullfrogs rimming the perimeter of Vashon’s ponds call for mates, Eckhardt, land trust director Tom Dean and volunteers with the Student Conservation Association paddle those ponds the land trust is working to restore — Fisher, Mukai, Meadowlake and Johnson — in pursuit of bullfrogs.

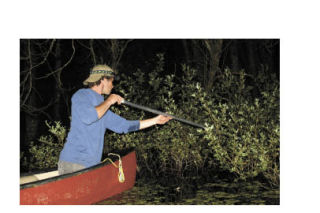

They carry a multi-pronged spear that they use to impale the amphibians, hitting each one they capture on the head to quickly kill it. The frogs’ bodies are then turned over to Gary Shugart, collection manager at the Slater Museum of Natural History at the University of Puget Sound, who dissects them to determine what the bullfrogs have been eating.

In their three years of bullfrog control, they’ve made a serious dent. Eckhardt recalled his first night-time visits to Meadowlake, when he used a bright flashlight to scan the pond’s perimeter in search of frogs.

“It was wild. There were eyes everywhere,” he said.

But Eckhardt, a committed conservationist, acknowledged that he didn’t relish the work.

“It’s never fun to kill anything,” he said.

Like most “invasive species,” as these frogs are called in conservation parlance, no one knows for sure how the bullfrog — Rana catesbeiana — got from its native home to the ponds of Vashon Island. Shugart, an Islander with a doctorate degree in ecology, said they were likely brought here in the 1920s or so for frog-leg farms, pond adornments and sport. In the south, “giggin’ for bullfrogs” — as it’s called — is a popular pastime, and their legs are a delicacy.

Now, according to Shugart and the land trust staff, these frogs have become nearly ubiquitous in Vashon ponds, triggering concern among conservationists that they’re upsetting the Island’s delicate aquatic balance. In some parts of the West, these aggressive invaders are wiping out whole populations of native amphibians and snakes, and articles about bullfrogs and their impact on native species — such as a recent piece in National Geographic headlined “Invading bullfrogs appear nearly unstoppable” — fill the conservation literature.

A few years ago, Shugart recalled, Mukai Pond “shimmered earthquake-like” because of all the bullfrog tadpoles that dived for the depths when he approached it. With one 18-inch-wide net, he scooped up more than 100 tadpoles. Using sample sizes, he estimated the tadpole population at Mukai at more than 5,000.

As a result, the land trust has taken on bullfrog-control as one of the important pieces of its mandate to steward the lands it owns or manages.

“It’s part of our due diligence,” Dean said. “You can save the land, but if you don’t manage it, it’s not going to benefit habitat and wildlife in the long run.”

“It’s easy to turn your back on something as difficult as a frog,” he added. “It’s much easier to pull Scotch broom. … But this is the tip of the iceberg. As conservationists, we’re really just started to focus on invasive species.”

On this particular night — a pleasantly cool evening in June — the land trust crew gathered around 9 p.m. at the large garage-like structure on the southwestern edge of Fisher Pond. There would be four boats going out that night — two to Fisher Pond, one to Mukai and one to Meadowlake.

It’s routine work for some of the veterans but not for the newcomers that night — Peter Evans and his father Jim Evans, land trust volunteers. Eckhardt chatted amiably with the two, demonstrating a blow-dart gun that was his first attempt at developing a way to nab the frogs and reel them into the boat.

The teams then split up, and Eckhardt and his teenage volunteer climbed into his truck to head o Meadowlake on the northern edge of Island Center Forest, the 363-acre preserve owned by King County and managed in part by the land trust.

Eckhardt parked as close as he could get to the pond, and in the fading light the two portaged their canoe over brush and deep, weedy grass to a small finger of water. They lowered their canoe and climbed in, then paddled under overhanging willows until they broke out into the open waters of Meadowlake — a quiet expanse of black water covered in places with mats of native pond lilies.

The osprey flew overhead, circling several times before settling onto a dark tree at the pond’s edge; Eckhardt said he’s seen it countless times at Meadowlake. A few bats soon appeared, performing their aerial acrobatics in search of insects.

Eckhardt explained the technique: Using a flashlight, you slowly search the pond’s rim until you see what you’re looking for — a pair of eyes shining in the light’s bright beam. He calls it “honing the frog eye.”

Sure enough, within minutes of paddling out into the pond and hearing the baritone bellow of a handful of males, Evans spotted a pair of eyes under a willow. The two paddled in that direct; they got as close as they could with the flashlight still holding the frog’s eyes, and Evans raised his spear. Seconds later, he pulled it back with a frog on the end, and Eckhardt quickly took it off the prongs and killed it with a block of wood.

“Our goal is not eradication but control,” Eckhardt said.

By taking out as many as they can each summer, the land trust crews are hoping to ensure few bullfrogs reach their full maturity — a whopping size of eight inches from head to back legs. The big ones, with the largest gapes, can swallow the largest prey and wreak the most havoc at a place like Meadowlake, he explained.

Evans and Eckhardt continued their quiet patrol, with first Evans in the bow of the boat spearing frogs and then Eckhardt. At one point, Evans impaled a frog that croaked as he handed it back to Eckhardt.

“This is the hard part,” he said as he watched Eckhardt kill it.

“It’s not their fault,” Eckhardt agreed.

In discussions with the board, he added, “We went back and forth on the most humane way. My philosophy is to do it fast, as fast as you can.”

A few hours later, as it approached midnight, the crews gathered together again at the garage at Fisher Pond and compared notes. Two were nabbed at Mukai, nine from Fisher and 10 from Meadowlake.

Shugard took each one and put it into a bag with dry ice, freezing them right away and thus preserving them so that he could take a look at their stomach contents in a few days. He would later find a small snake in one of them.

The number of bullfrogs they’ve caught this summer is down considerably from previous years, Eckhardt and Dean said, suggesting that the effort is making a difference. What’s more, they’re seeing a strong and healthy presence of Vashon’s native amphibians — red-legged frogs, Pacific tree frogs or chorus frogs, rough-skinned newts and Northwest salamanders.

“It’s encouraging,” Shugart said. “The literature says bullfrogs have wiped out everything, and they haven’t.”

But the land trust crews worry that bullfrogs populating private ponds on nearby properties will make their way to the ponds in the land trust’s preserves. And Dean said he expects that they’ll have to keep up this work if they want to see native populations continue to thrive.

“It’s key to educate people, because most Islanders — when you explain what’s going on — become real concerned,” he said.