Before some of the biggest story-driven, narrative video game titles ever to be played hit the market, there was islander Doug Sharp.

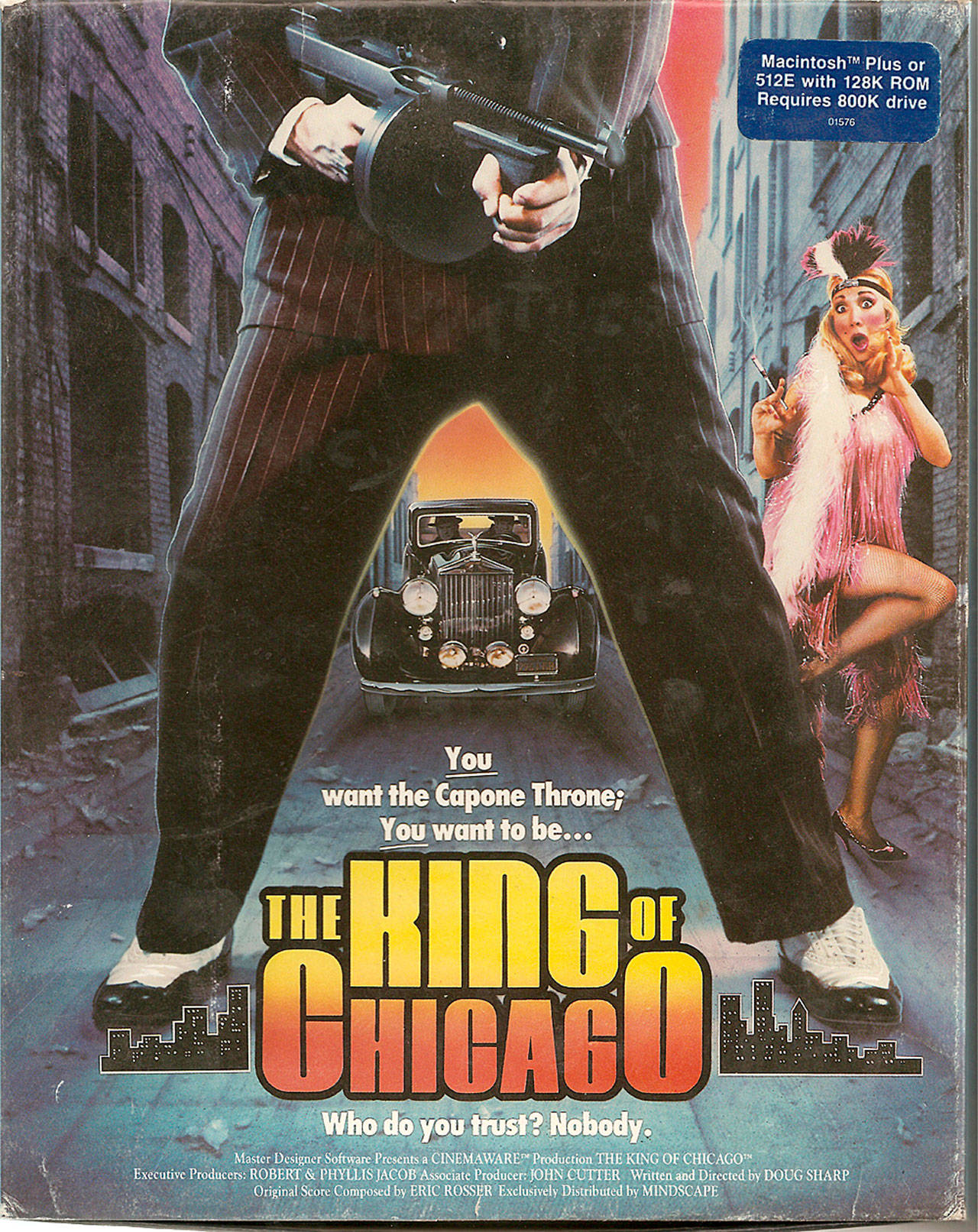

In the early days of PC game development, Sharp helped to create best-sellers such as 1986’s “The King of Chicago,” described by publisher Cinemaware as an interactive movie that told the story of a 1930’s mobster as he grew his forces to take control of the city. Today, graduate students and a doctoral candidate at The University of Washington Information School are using an archive of materials Sharp recently donated to Seattle’s Living Computers: Museum + Labs for a major research project.

“We’re trying to preserve this rich set of artifacts that rise up during the creation of video games that can tell how and why the story was made,” said Marc Schmalz, a doctoral candidate and research assistant working on the grant-sponsored project. Schmalz and his team are researching methods of preserving and categorizing the litany of technical documents, art, sound recordings and other materials amassed during game development in order to help players, professionals, students, libraries and museums better understand this vital form of digital media as it continues to emerge.

“People are really bad at preserving early works of pop culture. This effort is to try to come up with a better way to determine what needs to be preserved and the best way to do it,” he said, adding that Sharp’s collection of design notes, original character sketches, programming source code printouts, PR material, brochures and posters provides the team with a critical lens.

“He bothered to save all this, right?” said Schmalz. “It gives us a historical context as well as a focal point of what we’re studying, and so it’s very informative.”

For Sharp, who now writes science fiction, it is more than a matter of pride to give his collection to the museum.

“I’ve been carrying that archive around for over 30 years,” he said, expressing relief that it will be preserved in a permanent collection.

Some of the items Sharp kept from his “King Of Chicago” days included a box of molded gangster heads, which he had digitized for the game, animating the eyes and mouths by hand. He helped write the dialogue script — reviews of the time cited the story as one of the game’s most admirable strengths — and created the technology that rendered the game’s visuals.

“It was a burst of creative activity,” Sharp said.

One memory from the development of the “King of Chicago” that stands out to him was modeling for the game’s box art.

“A friend and I went out, and I bought gangster clothes and dressed up for the shoot,” he said. “Part of the fun is when you do work in games, it’s really intense, but a lot of fun. I was lucky to be in the industry in the mid-80s when one or two people could do an A-list game. Nowadays it’s a huge undertaking.”

Sharp said that “King of Chicago” sold 55,000 copies after it was released. And it still has a following: Retro game enthusiasts share videos of their playthroughs on YouTube, with many commenting that the game was ahead of its time. During his career, Sharp was also involved with the production of 1984’s “Chipwitz,” for Macintosh, an educational game in which users command robots to follow simple instructions. Material from that game will also join the collection at the Living Computers museum. Sharp said he has connected with fans who told him that the game helped to inspire an early love for computer programming.

“Kids loved it, adults love it,” he said. “I’ve had three people tell me they became computer science wizards because they played Chipwitz as a kid.”

Sharp said he is glad there is still an appreciation for his games, and now, a place for them in the growing canon of precedent-setting digital media.

“I was hoping that maybe one person would take an interest, but having it at the museum will be wonderful,” he said.

Dorian Bowen, Media Archivist at the Living Computers museum, said Sharp’s donation is an important chapter in the recorded history of computer software.

“That, combined with the oral history captured by the UW team, means that we aren’t just collecting a bunch of artifacts or a handful of software, [but] we are capturing and archiving an intersection of personal and professional history,” she said.