By BRUCE HAULMAN and TERRY DONNELLY

For The Beachcomber

March 12, 1959, was a typically cool, grey Pacific Northwest spring day in Olympia. The temperature only reached 52 degrees, and there was light rain, but as the day progressed within the Capitol building, tempers got hotter. The state Legislature had struggled for nearly three months to put together a funding bill to build the Vashon bridge. Now in the second special session, the House had passed the appropriations bill and sent it to the Senate, where final passage and a signature by the governor would make the long-awaited Vashon bridge a reality.

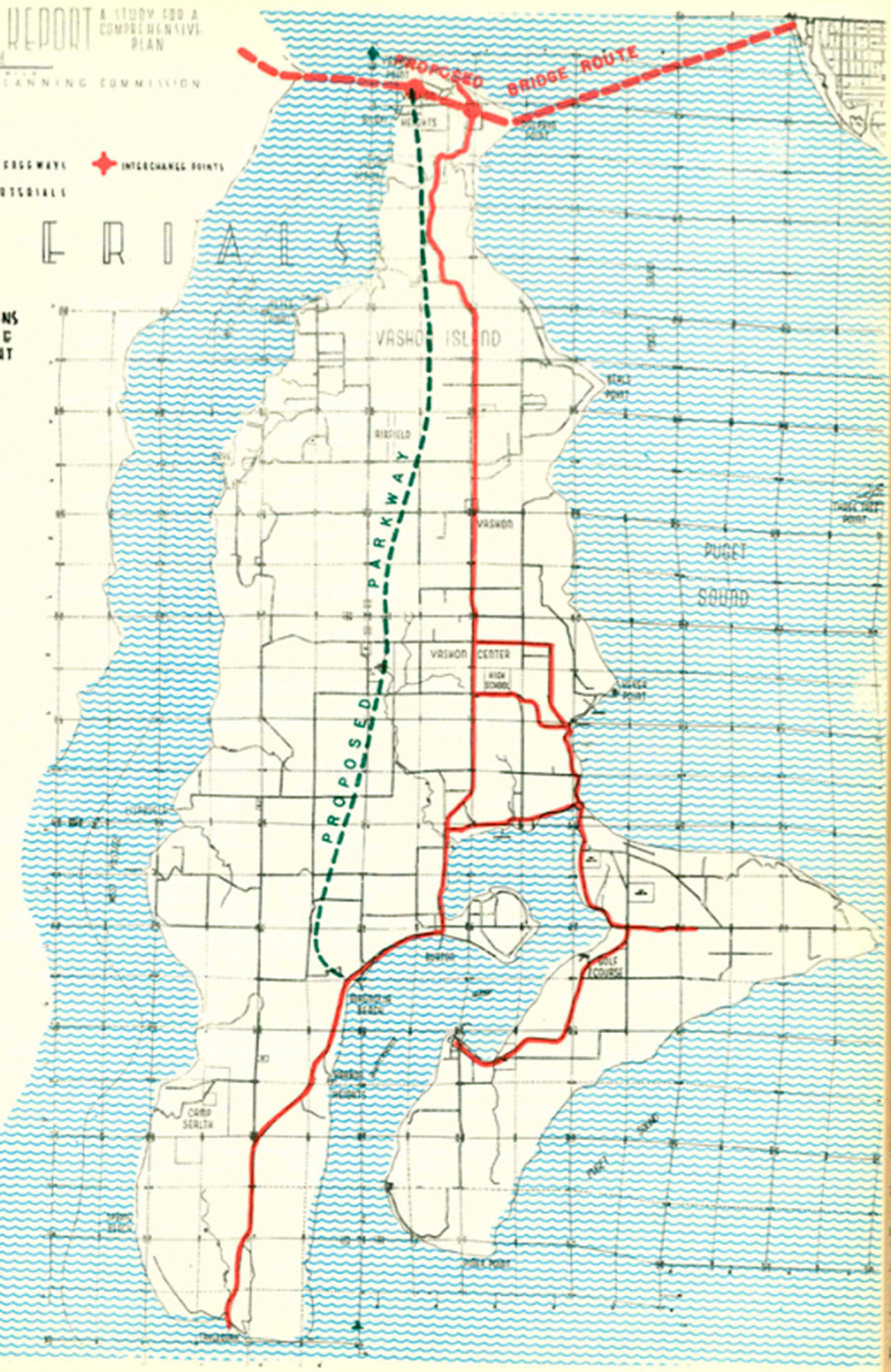

Homer Hadley, who designed the Mercer Island floating bridge that opened in 1940, had proposed a cross-sound bridge in the 1930s. The success of the Mercer Island bridge had led to the easy passage of the Cross Sound Bridge Bill in 1953, which approved construction of the Vashon bridge. A 1952 King County Planning Commission study, “Vashon Island Story,” projected a population of 50,000 for Vashon (it had a population of nearly 11,000 in 2010), numerous schools and parks, an industrial area on north Maury Island and a four-lane, limited access “Vashon Parkway” running down the middle of the island. But as costs soared and as the state encountered financial difficulties after creating the Washington State Ferry System, the funding to complete the Vashon bridge faltered.

Proponents of the bridge, including most Vashon islanders, thought the bridge would bring new and welcomed prosperity and growth to the island and to the connecting Kitsap Peninsula. The bridge would complete the long awaited cross-sound highway system and finally do away with Vashon’s dependence on unreliable and trouble-plagued ferries. This largely untrammeled support for the bridge was opposed by a few lonely voices on the island who thought the bridge would change the quality of island life. Others who opposed the Vashon bridge included the Pilots Association, whose members would have to guide large ships through the bridge; the Port of Tacoma, which saw a bridge as an impediment to its continued growth as a major shipping port; legislators from Eastern Washington who saw spending for Western Washington ferries and bridges as a waste of limited state dollars; and, perhaps most importantly, Seattle, Kitsap and Bainbridge Island leaders and legislators, who wanted the “Purvis Plan” that proposed a bridge between Bainbridge Island and Bremerton to link to the existing Bainbridge-Seattle ferry.

On this grey and rainy March day, the state Senate debated long and hard over the bridge appropriation. The House had twice approved the bridge bill by large majorities and sent a revised version to the Senate. Proponents of the bridge wanted a quick vote to secure passage of the bill and construction of the bridge.

Opponents sought to have the bill sent to the Senate Highways Committee, where it would be bottled up and die. Anxious to prevent the bill from dying in committee, supporters demanded the full Senate vote on the bill.

Lieutenant Governor John Cherberg, who served as the president of the Senate and was a proponent of the bridge, determined that the new House bill had significant changes from the original bill and ruled that the House changes had broadened the scope of the bill and thus must be sent to the Highways Committee in adherence with Senate rules. Standing at the very brink of success in building the bridge, supporters attempted to override Cherberg’s decision by asking the bill be heard by the Senate as a committee of the whole, but a vote on this proposal failed 21 to 28. Thus Cherberg’s decision to adhere to the rules and send the bill to committee effectively killed the bridge bill. The bill died in committee, was never returned to the Senate for consideration, and the Vashon Bridge was never built. This decision by Cherberg to follow his principles of adhering to the Senate rules rather than to his personal opinion saved Vashon from having a bridge, saved Vashon from potentially becoming another Mercer Island and preserved the rural character of the island.

John Cherberg is the unrecognized hero of Vashon Island. He was the right individual at the right place at the right time and with the right principles to make the decision that is one of the most important decisions ever made affecting Vashon Island. The decision not to build the Vashon Bridge, more than any other single decision, allowed the island to become what it is today

— Bruce Haulman is an island historian, and Terry Donnelly is an island photographer.