This Saturday, in conjunction with World Suicide Prevention Day, the University of Washington’s Forefront organization will premiere its short film “Thunderstorm in my Brain” about the death by suicide of 14-year-old islander Palmer Burk, to be followed by a suicide awareness and prevention training at the Vashon Theatre.

The film, whose title comes from a Facebook message Burk sent when reaching out for help, runs less than 15 minutes and offers a heartfelt look at his life and the circumstances surrounding his death in 2012. It’s a cautionary tale, focused on Forefront’s premise that most suicides are preventable, but firearms — which are responsible for the majority of suicides — rarely offer second chances.

“It’s excruciating to tell his story,” said Burk’s mother Kathleen Gilligan, who along with his sister, Garnet, is featured in the film. “But this will save lives. That’s why I’m doing this.”

After the film and a brief Q&A, a free suicide prevention training will be offered that organizers describe as “mental health CPR” — the steps everyone needs to know in order to help someone who needs it.

Forefront is a suicide prevention organization based out of the UW’s School of Social Work and was co-founded by Associate Professor Jennifer Stuber, who lost her husband, Matt Adler, to firearm suicide in 2011.

Adler, 40, an international corporate attorney, suffered from anxiety and depression that became so severe he was no longer able to work — but, according to a memorial biography written by Stuber at mem.com, not working only magnified the shame he felt over his “broken brain,” as he referred to it, and he began to think about suicide. His therapist refused to help when he revealed these feelings, and the negative stereotypes he believed about his mental illness and grief over what he perceived as the loss of his mind overwhelmed him, and Stuber was left to raise their then 5-year-old son and 1-year-old daughter without their father.

She was determined to change the story for others.

Getting Forefront up and running with donated funds after her husband’s death, Stuber’s initial focus was on improving training for mental health professionals. Partnering with Sue Eastgard, Forefront’s current training director and a 30-year veteran in the fields of mental health and suicide prevention, and state representative Tina Orwall (D-Des Moines), she helped pass legislation in 2012 (named for her husband) that requires all mental health professionals in the state to receive six hours of suicide prevention training every six years and was the first of its kind in the U.S. That was just the first of six successful suicide prevention bills that Stuber and Forefront have been involved with.

The most recent legislation, HB 2793 or the Suicide Awareness and Prevention Education for Safer Homes Act that was passed a few months ago, was aimed at suicide prevention training for pharmacists and firearms dealers/educators, and is how Stuber first connected with Gilligan (“Former islander worked to pass new Washington law that brings suicide prevention activists, gun rights groups together,” The Beachcomber, April 20, 2016).

“Kathleen’s story is so poignant,” Stuber said. “And it was just right on point to what we wanted to bring awareness to.”

At the heart of the legislation was the need for pharmacists, gun retailers and training professionals to receive suicide prevention training and materials in order to spot potentially vulnerable customers and be able to educate about and promote the safe storage of prescription drugs and firearms in the home. There were over 1,100 deaths by suicide in Washington last year, according to the state department of health, with firearm deaths accounting for over half of them, and poisoning (which includes prescription drug overdoses) 19 percent.

“Suicide can be a very impulsive behavior,” Stuber explained. “Safe storage is so important. This isn’t about gun control. It’s about safety and awareness.”

Awareness that Gilligan did not have four years ago. It was then that Palmer, who was well-educated in firearm use and safety but was suffering from depression, died by firearm suicide using an unsecured gun that Gilligan had in their home.

“Suicide was just not on my radar at all,” Gilligan said. “It’s not something anyone ever talked about. Looking back, I can see there were red flags, but I had no idea then.”

Stuber believed that Gilligan’s story would help get the message out in a way that training alone could not.

Enter David Friedle, a former filmmaking teacher at Nathan Hale High School in Seattle and soon-to-be administrator with Seattle Public Schools, and friend of Stuber’s.

According to Friedle, he had been looking for a social issue film to work on when he met Stuber. After learning about suicide prevention from her, he began to look into the data on students at his school as well as within the Seattle Public School system and was shocked at what he discovered.

“We had a big problem with kids having suicidal ideation,” he said. “I had no idea.”

The first thing he did was get his school to partner with Forefront to work on awareness and prevention training for all of the staff — which, according to Friedle, made a huge impact.

“All of the teachers were trained to recognize warning signs, how to talk to students and respond to them,” he said. “The number of students being referred for help tripled, and we know of at least two whose lives were likely saved because their teachers recognized the warning signs after the training.”

As for the film, it was designed to be a conversation starter, something to be combined with awareness and prevention training for the public as well as firearms retailers and educators.

“When you walk into a gun store, you see safety information, but nothing about suicide or self harm,” Stuber said.

Stuber noted that despite the shame and blame Gilligan has dealt with in the years since Palmer’s death, she has been a courageous and willing participant.

Gilligan noted that she is not a fan of seeing herself on screen or in the news, and is adamant about protecting Palmer’s privacy. But she also believes his story, and hers, will save lives.

“I don’t seek out opportunities to talk about this, it’s so painful,” she said. “But I feel like I have a moral obligation to help save others. Families have reached out to me to tell me that hearing my story has helped them. As long as that keeps happening, I’ll keep telling it, no matter how hard it is.”

Aside from Gilligan and Garnet Burk, the film also includes interviews with clinical psychologist and renowned suicide expert Paul Quinnett, as well as Doug Hartley, a National Rifle Association member and target shooter.

Stuber and Friedle are hoping to use the film in conjunction with Forefront’s training offerings to get the message out to the wider communities, but more specifically to gun owners.

Forefront’s focus is to re-frame how people view and talk about suicide, to de-stigmatize it, break down the taboos and to bring it into the mainstream as the public health issue that it is. Palmer’s story will now be a key part of its work.

“David and Jenn are using Palmer’s story to lead a social movement toward normalizing the conversation,” Gilligan said. “That is their mission. I’m doing it in memory of Palmer.”

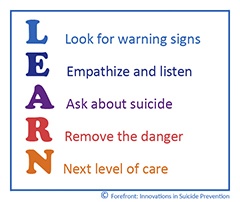

“Thunderstorm in my Brain” will premiere at the Vashon Theatre at 1 p.m. Saturday, followed by a Q & A with Stuber and Friedle and a suicide prevention training session led by Stuber. The training will follow the LEARN model (see infographic) developed by Forefront.

To RSVP for the event, go to tinyurl.com/WSPDVASHON.